Browse

III. Ethnography and Anthropological Image of Official Institutions

It is the 40th anniversary of reigning Taiwan. Photograph the changing savage customs, present-day status-quo and the scenery of savage land, name it ‘Looking into the Future of Savage Land’ and publish a photo album to commemorate this day.(註1)

– Savage Control Section, Police Department, Government of Formosa, 1935

September 10th, 1895, the happening of the first-ever meeting of the governor-general Kabayama Sukenori and the indigenous people attracted photographers to leave image documentation and witness the historic event. The photographer of the photos is military photographer Makoto Endo. The photograph of the governor meeting indigenous people were included in《征臺軍凱旋紀念帖(Commemoration of Triumph over Conquering Taiwan)》, which was later edited by Makoto Endo in 1896 and published with the symbolism of the start of colonial domination. The photo album documents series of events after the signing of Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, including how Japan was forming a military, boarding warships and crossing over the ocean, landing Taiwan, inside and outside Taipei city, Inauguration ceremony, and the process of going on a punitive expedition in the South.(註2)

Photography like governor-general meeting indigenous people has proved its important functionality at the beginning of Japan’s reigning of Taiwan. With the photography also left with a witness of the scene during the ongoing historical events, which later become materials of promoting colonial ruling policy propaganda. In other words, at the beginning of Japan’s ruling in Taiwan, the official colonizers’ photography of history has been the history of photography for the colonial officials.(註3) The images of indigenous people in Commemoration of Triumph over Conquering Taiwan in a way is a record of domination declaration for the colonizers of Taiwan, on the other hand also an advance announcement for Government of Formosa’s colonial policies that came later, especially for savage amelioration policies – the official ethnography that came with the process of policy promotion treated indigenous people as the subject to the policies and photography. The image documents would also become the colonizer’s material for self-promotion. The photograph of the governor-general Kabayama meeting indigenous people is included in Kabayama’s biography《臺湾史と樺山大将》in 1926(註4) and it is also included in《臺灣治績志》, which was an extension of the 1920s Government of Formosa historical document compile plan in 1937 and was written and edited by Government of Formosa official Ide Harai.(註5)

In the meantime, Colonial Anthropology uses a type photograph to form a critical ethnographic method for knowledge construction then. In April 1898, Ino Kanori published 〈臺灣に於ける各蕃族の開化の程度 (Taiwanese Indigenous Tribes’ Cultured Level)〉 on the Government of Formosa savage amelioration administrative officers assembled the Savage Intelligence Research Association.(註6) In his article Ino Kanori based on the research material collected since the arrival in Taiwan in November 1895, including his research on the whole island in 1897, which took 192 days in total, and purposed the categorization of Taiwanese indigenous tribes with discussions of evolution level in the views of comparative ethnography.

In the talk in Savage Intelligence Research Association, Ino first proposed a categorization table targeting Taiwanese savage tribes’ ‘categorized family’; he “pooled savages with similar qualities together, then based on the degrees of similarity to measure their consanguinity in the system.”(註7) In May 1898, Ino further published Taiwan Correspondence (issue 22) 〈臺灣通信〔第22回〕臺灣に於ける各蕃族の分布 (The distribution of Savage Tribes in Taiwan)〉 on The Journal of Anthropological Society Tokyo. The article includes not only the family categorization table of each Taiwanese savage tribes but further describes each distributed area and cultural features.(註8) Ino used a tree diagram of ‘group/tribe/section’ to divide Taiwanese Indigenous people into four groups, eight tribes, and 21 sections with the descriptions of the distributed places, physical features, cultural societies, and lingual features of each tribe. Ino’s complete report 《臺灣蕃人事情 (Things about Taiwanese Savage) 》 was published by the Government of Formosa in 1900.(註9)

Ino’s building of Indigenous categorization on Taiwan island uses the notion of tribes and divides into ‘Ataiya, Vonum, Tso’o, Tsarisen, Payowan, Puyuma, Amis, Peipo,’ eight tribes in total. If adding Tori’s research on the Yami tribe on Orchid island would constitute 9 tribes in total. The Government of Formosa used Ino’s research and the ethnography Things about Taiwanese Savage as building blocks and painted the map of the distribution of nine Taiwanese indigenous tribes which later became the foundation of aborigine categorization in Government of Formosa’s demographic statistics. Colonialism gradually brings together colonial documents regarding the categorization, demography, distribution, societal, cultural features, and imagery; the knowledge production of Colonial Anthropology thus arrived.(註10)

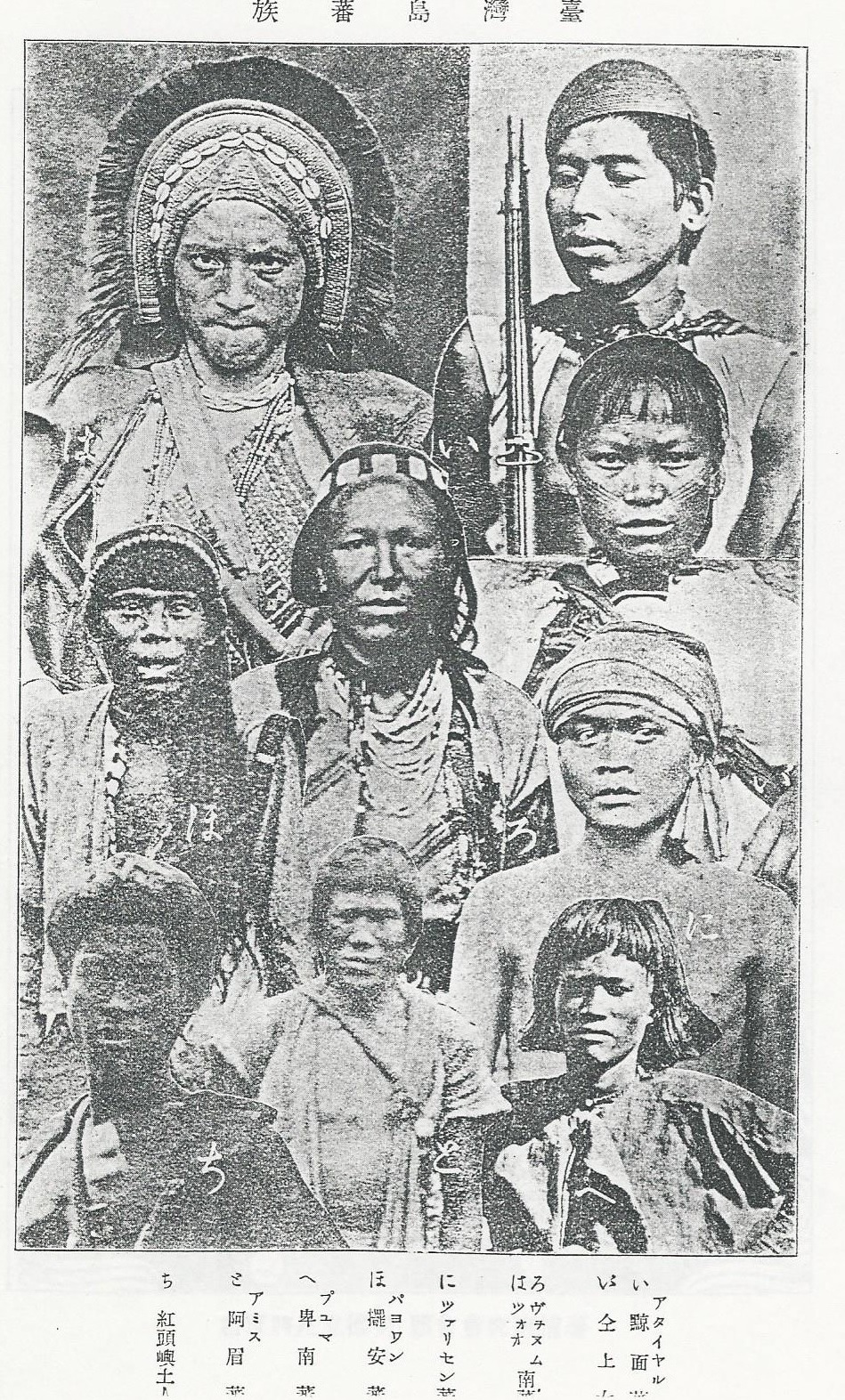

Ino did not seem to bring a camera into the field but still collected the image of indigenous people that was responsible for the Government of Formosa or came from other resources.(註11) A ‘savage tribes on Taiwan island’ image collaged with single representatives of each group with either a half-length photo or a headshot was shown in the opening ceremony of Savage Intelligence Research Association, displaying eight tribes other than the Taiwanese plains indigenous people. In the image, Atayal is represented by a male and a female, and Tso’o, Vonum, Tsarisen, Payowan, Puyuma, Amis, and Yami each is represented by male figures. The Atayal male comes from the Quchi tribe near suburban Taipei, and the Atayal female comes from Paran near Puli. Through the collage of photographs, the images of Taiwanese indigenous people are put together in the same category (‘the savage tribes of Taiwan island’).

After the image displaying (Fig. 5) of Savage Intelligence Research Association, either on the ethnography that is published by the officials or aborigine control monograph, the image documents of indigenous people has become a valuable content. For example, History of Civilisation theorist Takekoshi Yosaburō was commissioned by the Government of Formosa to write 《臺灣統治志 (Japanese Rule in Formosa)》in order to promote the performance of Japan’s colony ruling. Takekoshi based on Ino Kanori’s categorization to separately discuss each Taiwanese indigenous tribes in the chapter 〈生蕃狀態與蕃地開拓政策 (State of Savage and the Policy of Savage Land Development)〉. In the meantime, the attached photograph in the front pages of the book, divided by tribes, is using the photographs taken by the Government of Formosa and Mori Usinosuke to show their physical and cultural features with half-length front-facing and profile photographs.(註12) Takekoshi’s monograph is also later translated into English as Japanese Rule in Formosa for international promotion.(註13) The photographs of indigenous people in the English version are in the chapter The Savages and their Territory.

During the publishing of Takekoshi’s book, the Government of Formosa had changed the savage control policy. From the first governor-general’s Savage Amelioration policy, it has since 1903, become a lockdown policy – savage control has become a sole responsibility for the police departments, and a ban on savage territory was carried out to guard against interaction between indigenous and Han people. The situation was further enforced with military subjugation after 1906 after the sixth governor-general Sakuma Samata was inaugurated – he especially targeted Atayal tribes distributed in Northern Taiwan – between Yilan, Taoyuan, Hsinchu, Miaoli, and Taichung with multiple punitive expeditions. During this time, the book《理蕃概要 (Reports on the Control of Aborigines in Formosa) 》 that was published by the Government of Formosa’s Savage Office uses Ino’s tribe categorization and further describe Atayal’s natural surroundings, tribal groups, and cultural features. Meanwhile, an English version of discussions on the savage control Report on the Control of the Aborigines in Formosa was published in order to promote abroad.(註14) In this outside-promoting monograph extended the prior nine tribes categorization; a number of the photographs attached were shot by Mori Usinosuke with extra focus on images of Atayal people’s physical features, environments of mountainside villages, and cultural features. Other than the images of indigenous people, the action of how the Government of Formosa dispatched military army, police, frontier guard, and workers to work in mountains and to push forward the line of the frontier guards was also documented with photography. It was particularly mentioned in the English monograph that despite the current categorization divides indigenous people into 9 tribes, according to a new study that was done by the savage office, the three tribes ’Tsarisen, Payowan, and Puyuma’ which were in Ino Kanori’s original categorization should be included into Payowan; Sayi-Siyat could perhaps be included into Atayal or other plains indigenous tribes, which needs further investigations.(註15)

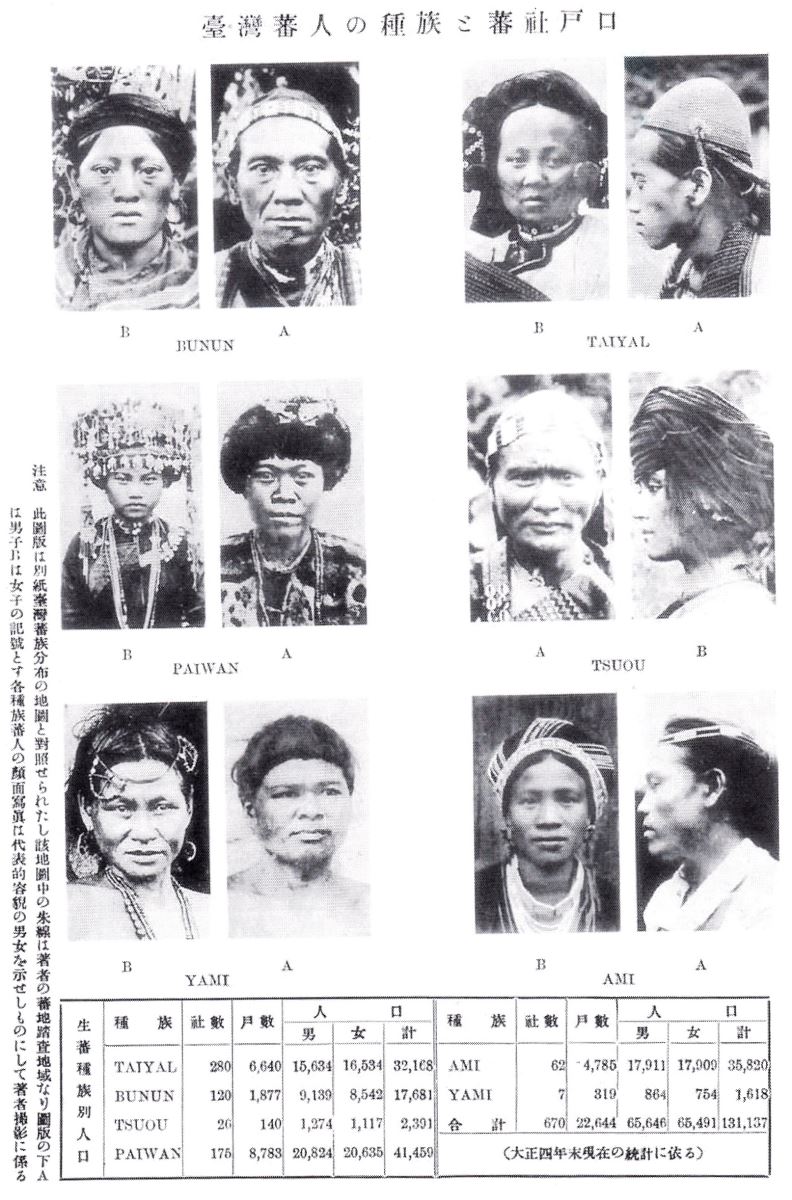

The research and recategorization by the savage office of the Government of Formosa would later reflect in the categorization of Mori Ushinosuke’s 《臺灣番族圖譜 (Taiwanese Savage Tribal Map)》, which was published by the temporary Taiwan old investigation agency of the Government of Formosa.(註16) Alternatively, one maybe should say that it is a revision from Ino Kanori’s categorization in order to reflect the official categorization of savage control administration from the Sukuma Samata era. The six-tribe categorization that was proposed by Mori Ushinosuke (Atayal, Tso’o, Vonum, Payowan, Amis, Yami) was also used as the principle to sort out the categorization of the tribes in the aborigine images. For example, the categorization is used in the sister issue of Mori Ushinosuke’s Taiwanese Savage Tribal Map – 臺灣蕃人的種族與蕃社戶口 (Taiwanese Savage Race and Savage Community House Registration) in 《臺灣蕃族志第一卷 (The Book of Taiwan Savage Tribes, Volume One)》, a demographic statistics categorization with the savage tribe demography from the six tribes, and in the meantime, with photograph attachments of male and female’s headshot or profile from each tribe.(註17) In 1915, the officer of the civil department, president temporary Taiwan Old Habit association Yoshida Uchida appointed Mori Ushinosuke to publish Taiwanese Savage Tribal Map to commemorate five years of savage control. Mori Ushinosuke’s Taiwanese Savage Tribal Map was initially set to publish ten volumes by tribes and themes, but due to unnamed reasons only has two volumes published in the end. The anthropological images from the first volume (Atayal and Vonum) and the second volume (Tso’o, Payowan, Amis, Yami) of Taiwanese Savage Tribal Map were photographs of Taiwanese indigenous people and their living surroundings which taken by Mori Ushinosuke during 1903 to 1915, with a few of them provided by the technicians from the Engineering Bureau, Agricultural and Industrial Affairs Bureau, and the Monopoly Bureau. Details of the photographer, the time and location of which the photograph was taken were specified. Some of the photographs were published earlier on the Government of Formosa’s publications or have circulated in the form of postcards. In Taiwanese Savage Tribal Map Mori Ushinosuke classifies images by tribes; other than villages and natural surroundings of peripheral landform, the most percentage of the images from same tribes but different villages are still front-facing portraits and images that show various cultural features (such as weaving, arrow shooting, housing, and headed scaffolding).

Mori Ushinosuke’s method of tribal anthropological imagery categorization, in reality, continued Ino Kanori’s principle of categorization in official ethnography and included more image with features of nature, landform, village, and culture within the same group. In the meantime, quite a few of the anthropological image which Mori Ushinosuke has taken includes ones where indigenous people were asked to pose a certain way to show specific cultural feature (such as man’s arrow shooting method and woman’s weaving method).

The arrangement of the images of indigenous people in the 1935 Savage Control Section Police Department Government of Formosa edited 《臺灣蕃界展望 (The Prospect of Taiwanese Savage World)》 continued to use the same arrangement method (… as its former).(註18) As a matter of fact, according to the foreword of The Prospect of Taiwanese Savage World which was edited by the Savage Control Section, the Savage Control Section consciously inherited Mori Ushinosuke’s 1915 Taiwanese Savage Tribal Map as an effort to present ‘the current status of savage control,’ and the changing ‘savage habits.’(註19) In 1935 the categorization of Taiwanese indigenous people made by the Savage Control Section Police Department Government of Formosa newly added the ‘Say-Siyat,’ which was recognized by Ino Kanori and Mori Ushinosuke a group of plains indigenous tribe descendants named Taokas who historically lived by the mountain but moved to the mountain to escape disaster.(註20) However, the official has them established a new indigenous tribe. Just like Taiwanese Savage Tribal Map, The Prospect of Taiwanese Savage World is edited with a tribal classification method. The images that were taken include the typical living landform, village, housing, living making, cultural and physical features of that particular tribe, also contain specific posed photographs that were supposedly asked to do so by the photographer.

Official photography was mainly for the purpose of witnessing savage control policy. On the one hand to steadily keep indigenous tribes and people from different mountains in photographs and later comb-through, edit, publish, display and circulate in either Taipei or Tokyo. On the other hand to use new scientific categorization, employ the method of tribal classification with ethnic group or tribe as units to further regulate indigenous people.(註21) Taiwanese indigenous people became like what French anthropologist and philosopher Bruno Latour said, the ‘immutable mobiles’ under the knowledge production process of the Government of Formosa’s savage control administration and Colonial Anthropology.(註22) The societal and cultural context of the tribe’s place of origin was pulled away; the image on the photograph is as if it were observations, interviews, and notes taken by anthropologists in the field on their notepads, or the measured numbers. The whole of the indigenous people’s life is turned into distribution maps, demographic digits, cultural features that could be single out and compared one by one, numbers of head-shape and shades of skin… in order to further analyze, induct, compare, solidify categorization of tribes and in the meantime marking their level of cultured.

From Savage Intelligence Association’s ‘Taiwan Island Savage Tribe’ to Synopsis on Savage Control,Taiwanese Savage Tribal Map and The Prospect of Taiwanese Savage World after the establishment of savage control institution and the aborigine image from Government of Formosa’s propaganda material; they all show relatively still image documents to present Taiwanese indigenous people’s ordinary status. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Government of Formosa changed its existing savage amelioration order and turn to aggressive methods, especially during the start and the end of pushing forward the line of frontier guards and the 5-year plan of savage control. In the process of frontier guard line’s surrounding net going forward, left an amount of documentary photography particularly about military action and punitive expedition towards savage villages. Atayal tribes that distributed in between villages in Yilan, Hsinchu, Taoyuan, and Taichung, the Taroko and Amis in the East, Payowan, and Rukai in the South were all shot/shot with the colonial government’s firearms and cameras. Just as the Commemoration of Triumph over Conquering Taiwan which was left after the Japanese invasion of Taiwan in 1895, these punitive expedition image documentation of savage control incidents, such as《臺灣生蕃種族寫真帖 附理蕃實況 (Taiwanese Savage Shashin Cho with Savage Control Scenes)》(1912),《蕃匪討伐紀念寫真帖 (Savage Brigand Crusade Commemoration Shachin Cho)》(1912),《討蕃紀念寫真帖 (Savage Crusade Shashin Cho)(1913),《大正二年討伐軍隊紀念 (Commemoration of Taisho Two Year Crusade Army)》(1913),《太魯閣蕃討伐軍隊紀念 (Commemoration of Taroko Crusade Army)》(1914),《霧社討伐寫真帖 (Wushe Crusade Shashin Cho)》(1931)… and so on were the documentation of the events but also a self-proof to the accomplishment of savage control plan.(註23) These images of savage control include not only the scene of military army and police team dispatch by the Government of Formosa, mountain war-strategic planform, mountain area military line-up and tactics practice but what anthropologist Peter Pels called the ethnographic occasion, where the incident employing camera actively presents the geographical location, natural environment, ecological condition, and cultural scene in the village.(註24)

IV. Typographical Photography and Colonial Anthropology

If it seems typical or has extreme features, then take a photograph. Take three kinds of photograph; front-facing, profile, and full length. Especially for the profile photographs, they are useful for measuring the angles of faces or noses.(註25)

– Mori Ushinoke

In 1912, Mori Ushinoke introduced his and Ryuzo Torii’s method of research in a thesis regarding the research method of Taiwanese indigenous people and explained the focal points of his photography. In the article 〈臺灣蕃族の調查に就て(Research on Taiwanese Savage Tribes)〉, Mori listed categories based on the stability and the workability of subjects; from items that are relatively stable to items that are easily changeable with environmental variables, such as: physical feature, ruins of antiques, mythological spoken words, Genesis or original legends, habits, language, local customs, old songs and ballads.(註26)

Within the category, the one Mori considered to be the hardest to change due to variables of time and environment is the physical features. The research items of ‘physicality’ are mainly indicating to ‘body measurement,’ especially nose shape, skin color, and features like hair and so on. Mori’s method is to measure a few people or tens of people, document the numbers and figures, look for their mean and make it to the standard type. In the meantime, document the standard type and ones extreme features with type photograph. When shooting the photographs, the priorities are three kinds of photograph; front-facing, profile, and full length. Especially for the profile photographs, they are useful for measuring the angles of faces or noses.(註27) In the research on physical features, other than the documentation of measurements, photography is also an essential method for presenting the standard types of physical features. The aborigine images that Mori took are shown in the male and female headshots of indigenous tribes in “Taiwanese Savage Race and Savage Community House Registration” from The Book of Taiwan Savage Tribes, Volume One, presenting front-facing and profile type features. (Fig. 6)

The type standard method which Mori Ushinoke used to shoot front-facing and profile physical features has been used in Ryozo Torii’s field research. The photograph of eastern tribes that shot in 1896 when Ryozo first came to Eastern Taiwan to investigate, and the single tribe photograph that was shot in 1897 when he came the second time to Orchid Island on a mission to investigate the Yami tribe, in both of which contain a number of front-facing and profile headshots, and full length photograph as a matter of fact belongs to an ethnographic method which obtains type photographs of racial standard types.

The same method as the photograph of standard typographical photography also had been seen on Ino Kanori’s ethnographical image, such as the collage photograph from the Savage Intelligence Research Association (Fig. 7-11). As of right now, we do not possess the record of if Ino Kanori used a camera, but his knowledge building on colonial anthropology and history has however regularly used image documents. Other than knowing the effect and power of impact that comes from anthropological images, Ino Kanori’s use of anthropological type photographs during the beginning of the Japanese Colonial period is actually entwined with the building of the theory of Taiwan’s anthropological knowledge in group categorization.

Ino likes to use image documents as an ethnographic method – in his fruitful number of anthropological and historical ethnographical theses, he often uses an ethnographical image that shows and goes with the theme of the article; apart from Taiwan, he also uses ethnographical images from all over the world to discuss comparative ethnography on the basis of type groups. Below discusses with the collage on Ino’s first publication of the research result on Taiwanese indigenous group categorization and level of progress at the Savage Intelligence Research Association in April 1898.

In the publish ceremony of Savage Intelligence Research Association showed the collaged image of ‘Taiwan Island Savage Tribes’ which was assembled with the eight tribes other than the plain tribes and half-length portraits or headshots of a single figure who represents their tribe. These photographs are shot roughly between 1896 to 1898; the number of books 《寫真帳 (Book of Shashin Cho)》 and《臺灣風俗寫真一括 (Collection of Taiwanese Custom Shashin Cho)》 Ino left still has preserved five original photographs. The collage of half-length portraits and headshots of Taiwan indigenous people below, on the left, are the photographs included by Ino in Book of Shashin Cho and Collection of Taiwanese Custom Shashin Cho, on the right, are parts enlarged from headshots on the left side.

Ino put the Quchi male and Puli Balan community female from the ‘Taiwan Island Savage Tribes’ image collage from the Savage Intelligence Research Association in the same categorized classification of Atayal. This kind of racial standard type image collage later become a consistent format for the Government of Formosa to represent Taiwanese indigenous people. In the official ethnographical photography – Mori Ushinoke’s Taiwanese Savage Tribal Map and The Prospect of Taiwanese Savage World from the police department savage control section, friends of savage control association show the organization of putting the same tribes from different areas together. Mori Ushinoke listed the leader of communities from the same tribe, though distributed in different geographical areas, in the same tribal category, such as how Atayal is included of the Quchi in the North, Wushe in the Center and even to Taroko in the East.

Other than anthropologists, the Taiwanese indigenous images that were used in Government of Formosa‘s savage control administration also used standard type headshot photograph, such as 《臺灣統治志 (Japanese Rule in Formosa)》and《理蕃概要 (Reports on the Control of Aborigines in Formosa)》. The indigenous image that was used on display in the expo was also presented with headshots from each tribe to show Taiwanese indigenous people. For example, the Taiwanese Savage Portrait in Paris Universal Exposition was re-illustrated based on Savage Intelligence Research Association’s Taiwan Island Savage Tribes and the Taiwanese indigenous image that was used in Taiwan Pavilion that was set up by Government of Formosa in the 5th National Industrial Exposition in Osaka used each tribe’s male and female headshots set side by side to each other to show their physical, and cultural features.(註28)

A single particular cultural character is used to be compared, images and photographs are partly retrieved, reset. Images have become an important ethnographic method in Colonial Anthropology to give away phylogenetic relationship between distant cross-over regional humans; or say, this presented a whole that constructed Taiwan Island Savage Tribes, Taiwanese Savage Portrait, or Taiwanese Savage Race. Ino Kanori cut and collaged headshots of leaders from each tribe, Tori Ryozo captured the portraits from Eastern indigenous tribes, or partial hairstyles and tattoo patterns to do comparative ethnographic researches, and Mori Ushinoke captured each tribe’s headshot and categorized them – they have done processes of translating, and the Government of Formosa (or Taiwan Anthropological Association) and Anthropology Society of Tokyo are the centers of calculation for the translation process.(註29)