Browse

I finally understand that (the naming of )Taiwan’s indigenous land, especially the east where was formerly named ‘The Darkest Formosa’ came with a good reason. I’ve been on several adventures and spent a fortune on three investigations in Taiwan in total, with good luck I’ve brought a silver lining to Eastern Taiwan and Orchid Island where they are lying in the dark.(註1)

–Tori Ryuzo, 1899

I. Foreword

In 1896 Japanese anthropologist Tori Ryuzo was sent by the Anthropology classroom of Imperial University to research on Anthropology in Taiwan. Tori’s research on Taiwan was the first time of which Japanese anthropologist apply photographic techniques on a colony. The field researched subject, as a result, left a considerable amount of dry plate photography. Photography gradually becomes an essential method for field researches under the development of Anthropology around the world, Tori’s knowledge building from Taiwan research has fully employed this new visual technology as well.(註2) Other than Tori Ryuzo, in the initial stage of colonization, a few other anthropologists in Taiwan such as Ino Kanori and Mori Ushinosuke both used visual technologies like photo-taking and photography exhaustively to construct the knowledge of Anthropology.(註3) The Imperial University Professor Tsuboi Shōgorō who encouraged Ino and sent Tori to come to Taiwan as Japan was taking over was primarily an expert on manipulating visual technologies in a way that’s shoulder to shoulder to the development of research and displaying knowledge of anthropology in Europe and America’s up-and-coming academic subjects.(註4)

When Tori Ryuzo came to Taiwan the third time in 1898 to research on the indigenous people in Taitung and Hengchun, he wrote a letter to Tsuboi Shōgorō in the field, explaining how he acquired an initial understanding toward the so-called The Darkest Formosa – Eastern Taiwan and Orchid Island after three expeditions (1896 Taitung and Hualien, 1897 Orchid Island, 1898 Taitung and Hengchun), and “with good luck I’ve brought a silver lining to Eastern Taiwan and Orchid Island where they are lying in the dark.”(註5) The ‘dark’ in Tori’s ‘The Darkest Formosa,’ or ’The Dark Savage Realm’ mentioned in his earlier article which was published in 1896 when he first went on expedition to Eastern Taiwan (Indigenous Tribes in Eastern Taiwan and Their Distribution)(東部臺灣に於ける各蕃族及び其分布), (註6) in a way was to patch up the various cultural forms and distributions of indigenous tribes in Eastern Taiwan which are lacking in the evidential ethnographic research; on the other hand also acting as a metaphorical expression for Tori whom ‘has brought a silver lining’ and explicitly indicating his tools he brought when his in the field: a box camera. Through beams of lights, the silhouette of communities of indigenous people in Eastern Taiwan was captured in camera obscura. After the films were developed, they become the first-handed documents that can stress the anthropological evidential science were undoubtedly on-site and were used as mediums to ascertain physical features and pick up cultural identification for acting as a comparative ethnographic research method.

At the beginning of the Japanese colonial period, Taiwanese indigenous people are not only subject to colonizers’ savage controlling administration, but the subject of the knowledge construction of the ethnography of colonies. In the process of embarking on colony governance and knowledge establishing, anthropological photographic archives started to develop. This article discusses official documentary photography and typological image through the analysis of the early stage savage governance institution and anthropologists’ ethnographic image and going forward, with the field photographic experience documented in anthropologists’ field diary, to further analyze the producing of the photographic archive and the response of the photographed.

II. The Photograph where Governor-general and Indigenous People Met

After the first governor-general Kabayama Sukenori announced the instruction of ‘Savage Amelioration’ on August 25th, 1895, starting from the amelioration of indigenous people in Tao ko kan, within the short time of six months, the instruction had spread to peripheral indigenous areas all over the island.(註7) The research he did at the time for Tao ko kan’s savage amelioration also later published in The Journal of the Anthropological Society of Tōkyō.(註8) This particular event not only sparked as the very beginning of the Government of Formosa’s policies for savage amelioration but became the starting point for Taiwanese Studies in Modern Japanese Anthropology, alongside with the emergence of a colonial anthropological image.(註9)

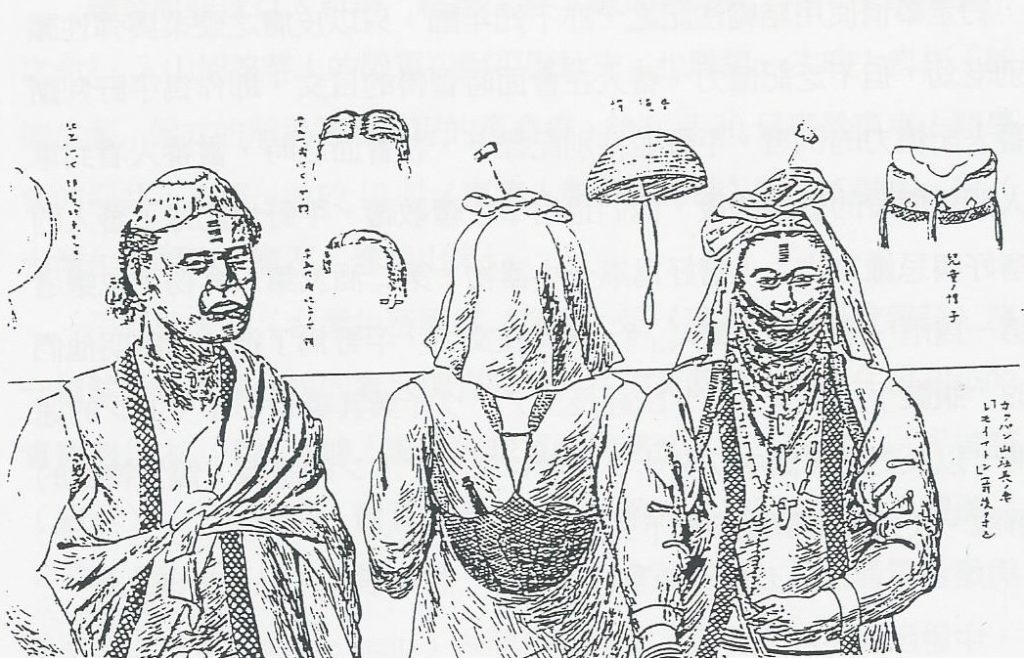

The report Inspections on Taiwanese Indigenous People which was written by ground force Second Lieutenant Akiro Hirano who was ordered by the governor-general to delve into the mountains and recruit indigenous people was the first on-field survey report on Taiwanese Indigenous People in The Journal of the Anthropological Society of Tōkyō. In the fieldwork report about Taiwanese indigenous people, Akiro based on criteria like savages’ affection level towards the Japanese army, garments, tongues, physical features, education. Etiquettes, and amenities, and briefed on various physical features and cultural traits on indigenous people who attended the amelioration ceremony. In the report, Akiro attached the half-length portrait of the president of She-Na-Cheng Community Watanawi and his wife Lemoimaton with commentaries on their garments and physical features. (Fig. 1)

The report that Akiro published has immediately gotten revised by the member of Anthropological Society of Tokyo and employee of Government of Formosa Ino Kanori.(註10) On January 1896 Ino Kanori published “The Local Savages of Toa ko kan (大嵙崁, 地方に於ける生蕃)” in The Journal of Anthropological Society Tokyo to respond to Akiro Hirano’s report.(註11) The article which Ino published also included a needle-point portrait sketch of the photograph where three indigenous people went to the Government of Formosa to join the meeting. The sketch is speculated to be drawn by the painter of Anthropological Society of Tokyo Ohno Kumo, who did the sketch based on the photograph. Later on, the picture of indigenous people’s physical and cultural features which Tori Ryuzo used along with his article when he published his first research paper on Taiwan was also drawn by Ohno Kumo based on the actual photograph that Tory has taken.

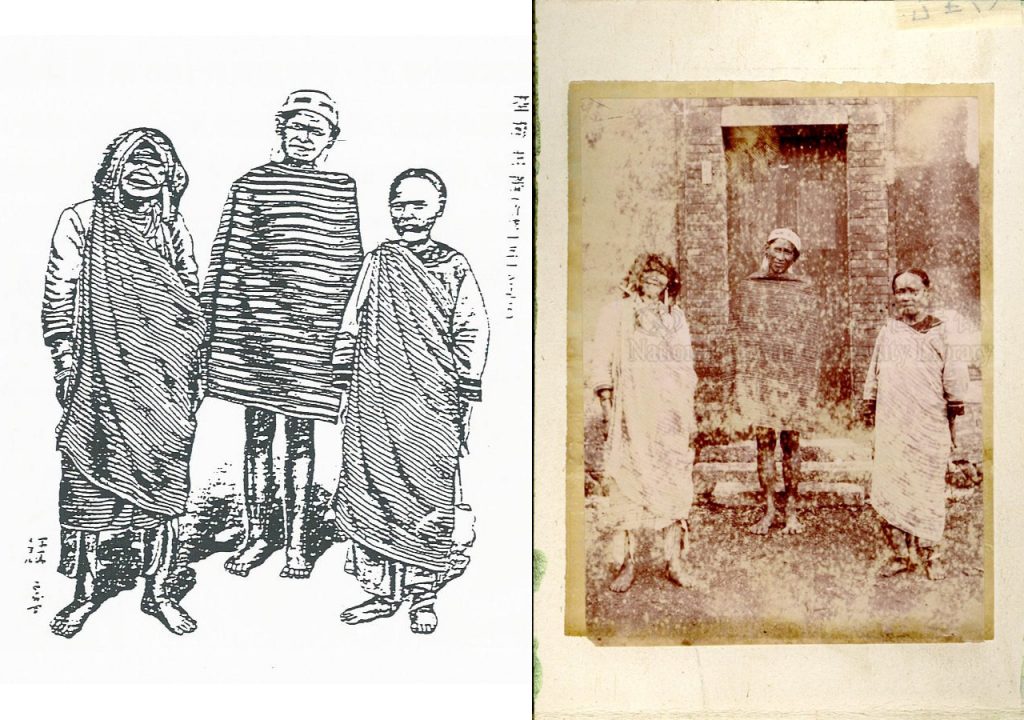

The discussions rounded the ceremony in Tao ko kan’s ‘savage amelioration’ between Akiro Hirano, and Ino Kanori was a colonial issue in The Journal of Anthropological Society of Tokyo. During this particular event, the question (ethnic group categorization) that has taken concern in Colonial Anthropology and the theoretical resources and analytical methods using in discussions has started to come to its prototype. In a research paper that discusses from Tao ko kan indigenous people’s physical, lingual, cultural features to racial categorization, the photograph which Ino used is taken on 10, September, 1895 right after when governor-general Kabayama Sukenori’s declaration of Savage Amelioration, he met and greeted the five Atayal indigenous people from Jiaoban Mountain and She-Na-Cheng community in the Government of Formosa. If comparing Ino’s portrait sketch and the actual photograph that Ino’s article based on, discovery can be found that Ohno Kumo from Anthropological Society of Tokyo erased and left blank space on where the door, stairs, and walls originally were, meanwhile accentuated the cultural features of indigenous people’s physic and clothing but kept the feature where one of the indigenous people was wearing a Han women’s coat with embroidery on the seams.

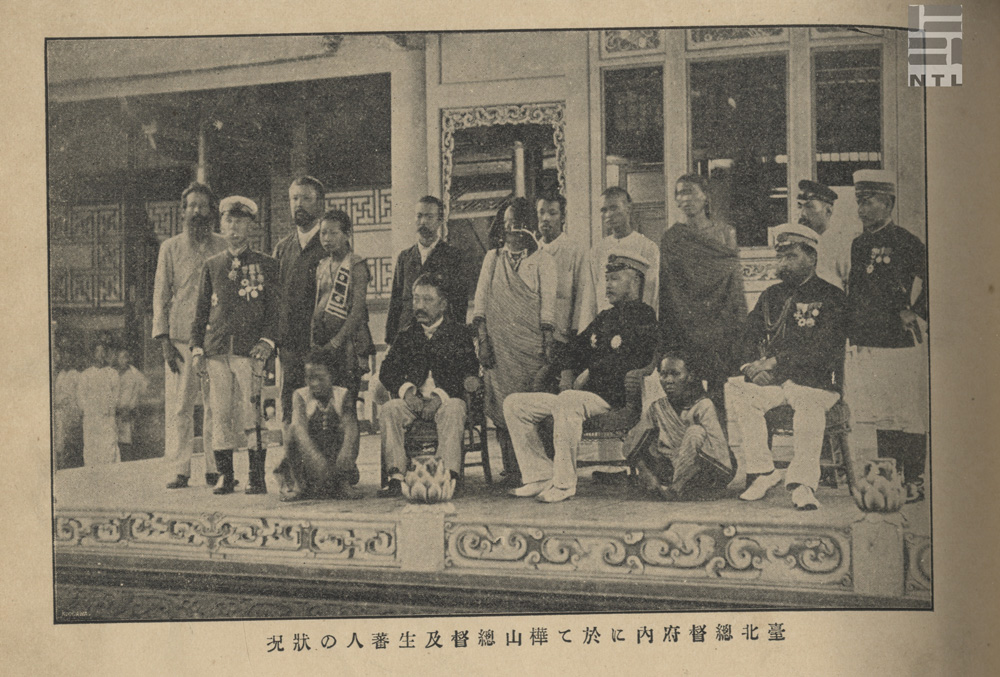

When the Savage Amelioration was ongoing, Tao ko kan’s Atayal people had been into Taipei city to meet with the governor-general and taken at least three photographs during (see the photographs attached to this article), thus left the image documentation of indigenous people from earliest colonial reign. One of the photographs Governor-general Kabayama and Indigenous People’s Earliest Meeting (Fig. 3) is a group photo of five indigenous people, the governor-general and high-ranking officers. The other one Taiwanese Indigenous People (Fig. 2) – a group photo of three indigenous people that was taken by the wall inside the Government of Formosa is a file that was published by Ino Kanori on The Journal of Anthropological Society Tokyo. Moreover, the indigenous people who came into Taipei city to meet the governor-general also left another photograph on the same platform where they had taken the photo with governor-general before with the name The Savage Convention that was shot in Taipei Government of Formosa (Fig. 4). This one was shot in-between the group photo with the governor-general, another photograph with only the five indigenous people and a translator. Three of the five indigenous people even sat on the seats of governor-general Kabayama Sukenori, chief of civil department Mizuno, and chief of navy Kakuda Hideshiro; the five stared at different directions, chatted and laughed in an innate manner. If compared with the governor-general meeting photo; one presents governor-general Kubayama Sukenori as the focal point with indigenous people either squatting or standing between governor-general and high-ranking officers from the Government of Formosa, and with everyone displaying a solemn look, focusing their eyesights on the left side. Maybe there was another camera on the left side?(註12) The other is relatively free and liberated in a relaxed atmosphere and seems like a picture that was captured by the photographer in a moment of frolicking. It is also a rare image of indigenous people where the figures in it are showing smiley faces; it is hard to see smiles on indigenous people on photographs whether it was captured in a photo studio or in the fields.

After the instruction of Savage Amelioration was ordered by the governor-general in 1895, the early stage of Japan’s reign over Taiwan; the three photographs that was shot in the Government of Formosa: Taiwanese Indigenous People, Governor-general Kabayama and Indigenous People’s Earliest Meeting, and The Savage Convention that was shot in Taipei Government of Formosa, the development and careers of them seemingly prognosticate the start of colonization and ruling later on and how the images of Taiwanese indigenous people would be produced and circulated.

‘Taiwanese Savage’ becomes the material for the knowledge production of Colonial Anthropology and through anthropologists like Ino Kanori, Tori Ryuzo, Mori Ushinosuke, and others, develop the ethnographic method of using images of indigenous people as tools to continue producing and accumulating colonial anthropological indigenous people images. Governor-general Kabayama and Indigenous People’s Earliest Meeting, and The Savage Convention that was shot in Taipei Government of Formosa were first put into military photographer Endo Makoto’s collection album 《征臺軍凱旋紀念帖》, then reproduced later in various official ethnographic reports. The colonial government would later follow former with their savage control administration and shot, collect, and publish many images of indigenous people. Furthermore, through the copying and postcard producing by officials and photography studios, these postcards are either sent back to the country of the colonizers or abroad.(註13) Through Colonial Anthropology, ethnography from official institutions and photographic postcards, the producing and circulating of images of indigenous people gradually accumulates something that maybe could be called photographs of aborigines as colonial archives.