Browse

Sylvie Lin: Your early works often revolved around one single element (light, sound, etc.). Then you moved toward installations of multiple media through certain cultural anthropological approaches with a persistent interest on materiality. Please talk about such an artistic evolution. How do you elucidate the relations between your artistic concepts and the anthropological approaches represented through installations?

Ting Chaong-Wen: The function of light is indispensable for visual arts. The idea of photon proposed by the Epicurean School before Christ represents a pre-modern mystic theory. To a certain extent, it still attracts me. We may try to imagine an eternal beam set forth from the depth of haze-like time, being reflected to the modern times and manifesting in our ordinary life. Among realistic painting, divine rituals, historic archives and social spectacle, the beam still advances along traces of time, constituting attachments and vehicles wherever it passes. For my work, light provides proofs of the existence of time’s movement. For me, “time” has certain plasticity. I’m often fascinated by history and linger over it. For my work, this gradually leads me to try to capture events happening momentarily and sealed in time and space by transforming and hiding subtle things in internal forms. I call this stirring “time” itself. Similarly, an artist captures after-effects overflown from all kinds of substances at the moment of “affection”: it’s something hybrid combining “sensibility” and “reality”, inciting me to carry out work of achieving plasticity in addition to analysis and writing. This can be seen as the turning point of my creative method. And contemporary artists are similar to anthropologists. As artists, we rely on anthropologist investigation methods like field research and observation. Anthropologists also often use “boundary thinking” as a reminder to them. According to the concept, what we see in front of us “is not always taken for granted”. This coincides with my view and thinking about historic flow. History also results from mutual influences of diverse factors in specific contexts. Returning to “history” in order to examine the phenomena we see or the process of culture development: this is arguably the core of my art-making in recent years.

Lin: Regarding materiality, a central aspect of your oeuvre, you mentioned “the composition within materials directly references spirituality and culture, whereas the artwork introduces elements of uncertainty, unpredictability, and fluidity to the material.” Please take few examples from your works to illustrate such idea.

T: Materials themselves have cultural symbolic meanings. As an artist, part of my work consists of simulating essences of “things” and pondering spirituality of objects. For example, “The Collapse of Cool (2013)” explores characteristics of concrete. Regarded as an ordinary material, concrete is important for its anti-seismic effect; it resists natural catastrophes (earthquakes, mudflows) rather efficiently. In terms of art production, I’m interested in concrete in its symbolic sense; it’s about how to disclose and analyze its material and its quality as a tool. I interpret the accessibility of the existence of artistic nature in such reactions and operations through a single material’s reactions to physical and chemical movements. For its long history as a material in civilization, concrete attests to the formation of Taiwan’s cultural modernity. According to archeology, the first concrete construction defined in a broad sense is the Fort Zeelandia (Anping Castle) built in a shoal in Kuan-shen in today’s Tainan in 1624 during the Dutch colonial period. Colonizers introduced new construction techniques to create a new spatial symbol of their reign. Since then and the Japanese colonial period, Taiwan’s engineering development has been based on attributes of concrete as an economic and highly efficient material. Colonialism took place along with modernity and influenced modern architecture’s aesthetic correspondences to cool and low-key impressions.

Therefore, “The Collapse of Cool” takes the form of installation with concrete being poured live to make the viewer feel the model’s formal changes gradually produced as time goes by. On the other hand, I use earthquake statistics recorded by weather bureau and turned it into sound waves producing stirs on the concrete’s pouring surface, thus representing possible concurrences of violence of catastrophes and engineering creativity. By poeticizing materiality, I capture traces of art’s origin within works to explain “elements of uncertainty, unpredictability and fluidity in the constitution of a material” and demonstrate the method established in terms of artistic thinking.

L: You made several residency projects around the world; the sites range from Sapporo, Seoul to Paris with their distinct geographies, characteristics and cultures. As an artist in residency, how do you approach foreign localities and search out methods of investigation and artistic practice? And please talk about the residency experiences that cast strong impacts on you.

T: Due to cultural differences and language barriers, when an artist takes on a residency overseas, his or her identity as an “other” is more similar to that of a “prehistoric man” hidden in ordinary life. To a certain extent, for me, this relies largely on the primitive instinct to carry out tasks of exploration, collecting, understanding and creation in different cities or regions. Yet, meanwhile, the artist in residency is also an anthropologist making field research and interviews, especially work about archive archaeology. Archive is seen as a place of the past, containing traces of collective memories of a country, a people or a group. Through archive, an artist can also understand the relations that affect our past, present and future. Archive is not only the record, reflection or icons of an event, it also forms the event itself and thus influences the present and the future.

Let me take my residencies in Sapporo and Seoul as examples to discuss artistic practice. Both projects in the two cities involve the idea of “place”. My residency project in Sapporo was in wintertime. At the beginning, I got to understand the place through Hokkaido’s natural history, geology, ethnology, archeology or traces of recent times. Hokkaido is situated in the north of Japan. Compared to the culture of Japan’s largest island, the region’s history is more connected to culture of the north-eastern region, pre-modern Eurasia culture, Jomon culture, Okhotsk culture or Aynu culture. Culture arguably influences art most directly. When an artist from a subtropical country stays in Hokkaido and sees the pure white snow, he or she comes to understand the dreamlike fantasy such a white sphere brings to tourists. However, for Sapporo residents, this means cruel reality. Far from some romantic imagination, snow puts trials to all beings. In confronting local history, one finds stories hidden in Aynu, the Republic of Ezo or the Sakhalin region during the Second World War. That’s why an artist has to reside personally at some place and try to become an “insider” from an “other”.

As for Seoul, it embodies a sample of urban life that is faster than real-time. City is a kind of relic of modern life. Spectacles of consumer culture are omnipresent in the entire city of Seoul. I picked up wastes around the industrial area where the artist village in Seoul was situated. Through a modernologic way, I dug out objects with cultural symbolic meanings, such as military boots of the Korean Army and plastic tea tables printed with patterns of mother-of-pearl lacquer. I juxtaposed them with the volcano rocks I picked up on Ulleung-do Island. The icons respectively represent a certain subjectivity of Korea. I moved the objects encountered by chance or obtained spontaneously objects from the streets outside into the studio. Through recombination and alteration and by means of affectional and spiritual levels hidden within materials, the whole process is an attempt to reveal the “identity” of a place and how it influences local residents. In short, I’d like to represent how contemporary art gets closely related to the production of reality.

L: In “The Rhyme of Forms (2014)”, “Civilization Laboratory (2013)” and “Systematology (2012)”, you explore anthropological, historical, colonial and urban issues of Tainan, the city you live currently. How do you view the city as a locus of intricate historical, societal and political influences? What kind(s) of “script” (a term you mentioned in describing your artistic idea) do you attempt to represent through your works and projects about the city?

T: Tainan has been ruled by the Dutch Empire, the Ming Dynasty (Zheng Chenggong, or better known as Koxinga國姓爺), the Qing Dynasty and the Japanese Empire before being taken over by Kuomintang after the Second World War. The 400-year history can be seen as epitomizing the history of Taiwan. Whether regarding official or folk cultures, Tainan preserves abundant dynamism. Artists can dig many interesting stories here and traces preserved in local ordinary life left by history always appear through diverse archival forms. As an artist, I work on revealing sensible experience contained in such archives and generating a Blind Field through my works, a field that extends beyond a reservoir of memory. In appreciating the works, the viewer’s feeling and imagination can flow freely while his/her consciousness about the current state of existence would be activated through such retrospection over historic archives.

“Systematology” you mentioned was made during my residency in Bamboo Curtain Studio; the discussion is extended to include Tamsui and Tainan, two old cities respectively in the north and the south of Taiwan, and penetrates their food cultures and histories of living, presenting relations between ecology and consumer culture. Besides, through the work, I attempt to elaborate on how painting from nature continues to exert influence today and express shifts between the artist’s mind and the reality. As for Civilization Laboratory, it presets two parts. One is “Tsuo Chen Man Project” with the mudstone area of Zuozhen(左鎮) in Tainan as its context to investigate the history of local fossils. The other is “History of Hybrid Culture Movements” resulting from the research during my residency at S-AIR in Sapporo in 2013; it is built around visits and studies of natural, cultural or historic traces left in Hokkaido. Both works are about how to re-constitute and measure culture through artistic angles as well as historic connections among its materials. “The Rhyme of Forms” is an installation in commercial spaces. The choice of jute as material is for tracing back to Tainan’s linen manufacturing industry in the Japanese colonial period. The work re-examines historicity contained in materials. I combined fabric of cloth, binder and aggregate to form concrete before burning cloth contained in it, so that the concrete keeps the spaces where the fabrics lied. These are like pieces of “fossils of artificial clothes”. The clothes once thrown away or without masters are like expatriates and return to be exhibited in commercial spaces. Through such process, I attempt to provide reflections about the relation between objects and the self.

I’m interested in the history of a site, including human activities there and especially stories hidden behind personal histories, which are presented before an artist’s eyes in a form more akin to “scenario”. For example, my recent project is about the space of Tainan County Council of the past. I particularly attempt to invite the public to enter the council building and learn the history of local autonomy through the works. The project series’ title is Site of Consciousness, indicating contemporary art is an ability to perceive the environment and the self, and to capture actual changes and flow at the site relies on our awareness and perception of the shifts of people, things and events there.

L: Please talk about your upcoming residency project in Peru. What aspects of the place will you focus on? What approaches will you take; what actions and investigations will you carry out locally?

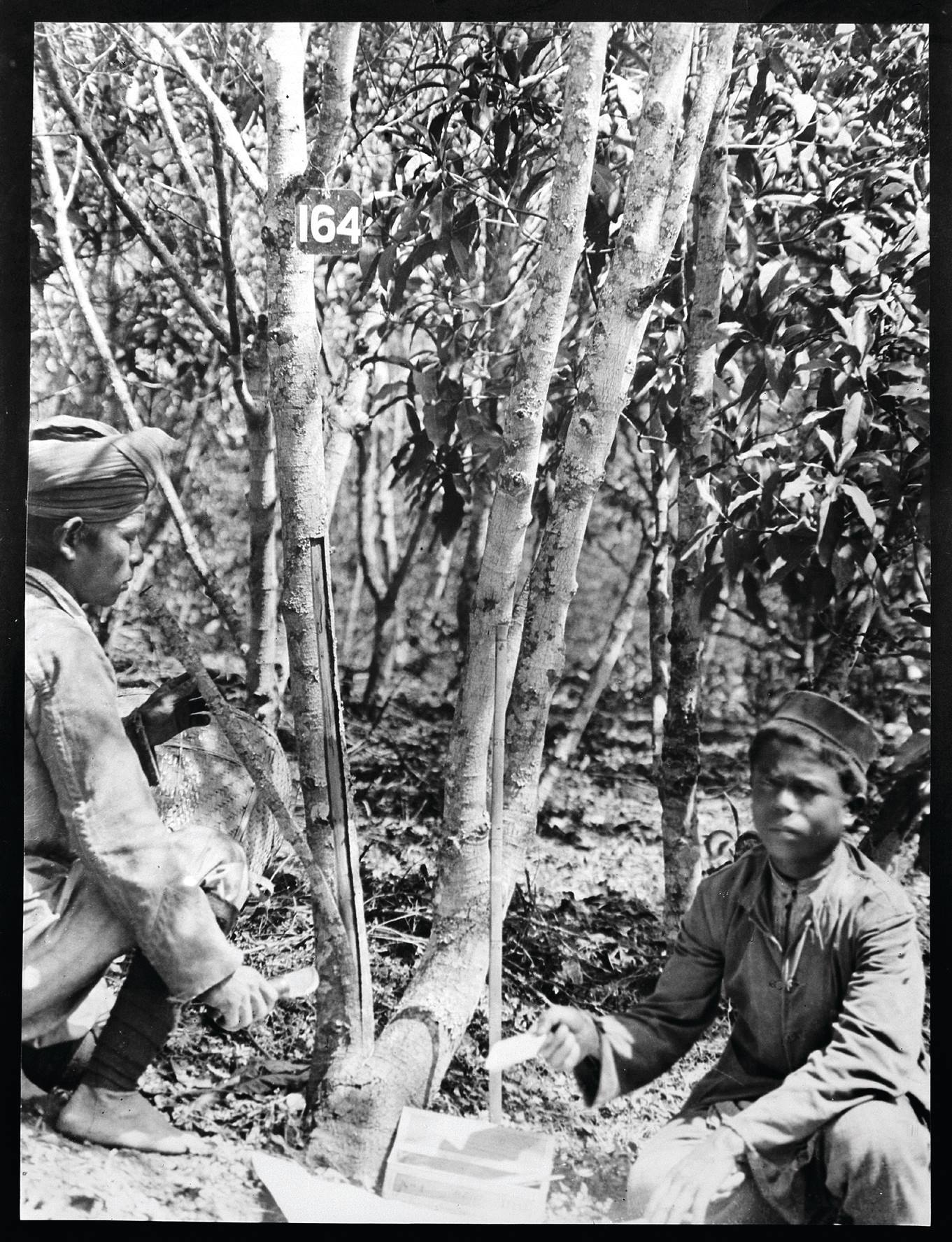

T: The Japanese colonial period between 1895 and 1945 was the phase of importation and experimentation of tropical plants on the largest scale in Taiwan’s history. Hundreds of tropical plants represented romantic imagination of tropical colonization evoking the Japanese Empire. In the 19the century, cinchona tree (幾那, 機那, 規那 or キナ皮 in Japanese, first introduced from the South America to Europe in the 17th century) formally entered laboratories and great manors in Europe. In the second half of the century, the French, the British and the Dutch Empires began to transplant cinchona tree sprouts and seeds into their own countries or colonies, regardless of embargoes on importation set by newly independent republics in Latin America. “Cinchona Bark Science” (a.k.a. “規那學”) which investigated such tree’s plantation also became a famous doctrine for the empires. Scientists of the colonizing countries tried to distill alkaloid contained in the bark to prepare quinine (貴尼涅、幾尼涅、規尼涅、キニーネ in Japanese). Colonies in Asia were mostly tropical countries plagued by malaria and calenture. During the colonization process, Europeans incidentally discovered that native Indians of South America used cinchona bark to cure fever and quinine was the only remedy for curing and preventing malaria before the invention of synthetic vaccine.

Since the early 1920s, Hoshi Pharmaceutical of Japan, the second producer of quinine at the time, has also started its plantation business of private farmland in Taiwan. With the wave of cultivating medicinal plants, the island which used to be plagued was turned into a treasury of pharmaceutical industry. Thanks to its topological diversity, the ecological environment with diverse climates (tropical, subtropical, temperate and cold) between plains and mountains was perfect for growing such trees. In Taisho 7, Hoshi Pharmaceutical’s Director Hajime Hoshi purchased 3,000 square kilometers of land in Peru for growing cinchora; Sawada Masaho, an expatriate Japanese technician in Peru, then visited Taiwan for investigation and obtained a convincing proof for planting such tress in Taiwan. In the next year, through the Department of Promtion of Industry, Hoshi asked Yasusada Tashiro to estimate Taiwan’s environment, leading to the discovery of a virgin forest on the hillside of Wuwei Mountain (part of Dawu Mountains[大武山脈]) of Chaochou County(潮州郡), Kaohsiung State; its soil, climate and humidity made it an ideal place for growing cinchona trees. In 1924, Hoshi Pharmaceutical went on to set up a base for cinchona afforestation industry in the area near Jhihben Hot Spring(知本溫泉) of Taitung T’ing(台東廳). The commercial ambition of a private enterprise took over the government’s will to continue the cinchona business in Taiwan.

Following the observations above, I developed the idea of Cinchona Bark Science of the Empire for my residency titled Micro-historical in Peru. I attempt to explore Hoshi Pharmaceutical’s plantation land for cinchona tree at the north bank of Río Huallaga by investigating the National Botanic Garden in Lima and to make research of related presentations and studies by visiting Biblioteca Nacional del Perú, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, the Lima National Museum, etc. As Peru’s national tree, cinchona tree drifted over the ocean and across half of the Earth to arrive in Taiwan. The relation between the empire and botany is a proof of the complicated process of modernization through colonization. With my project, I’d like to respond again to relations between the dispersion of species and post-colonialism in an imperialist and globalized context from the perspective of Taiwan.