Browse

This is an old piece of photographic film whose colors have been corrected in an eerie fashion, but which nevertheless records two activists dear to me. In the picture, one can see W.E.B. Du Bois, who has accepted the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries’ invitation to come to Beijing, meet Premier Zhou Enlai, and make a speech at Peking University. During this visit, Du Bois witnessed the enormous social transformations that were sweeping the country; as a devoted communist, he believed that the forces of colonialism and racism would one day be defeated, and that comrades in Africa and Asia were vital allies to this struggle. He took advantage of the talk to mention that a rising Africa would stand tall, emerging from 500 years of humiliation to face a rising sun.(註1) It is hard to say whether Du Bois’ choice of the rising sun as a metaphor stems from his investment in “light,” or whether he meant that, geopolitically, the future must be entrusted to the East.

In order to better grasp the meaning of the imagery of the rising sun, I have focused, in recent years, on the region of West Africa, which was his final battleground after leaving Beijing and before he passed away.

The scorching, West African sun is so formidable that without frequent rehydration, one’s body will quickly be exhausted. Aside from this, an intermittent electricity supply was a serious strain to my research. From Nigeria’s megacities to Togo’s tiny villages, each time I conducted fieldwork, I had to prepare more batteries and external power devices. The first time I traveled through Africa, I quickly realized that those who were assisting me with logistics, as well as my hosts, all used phones branded Tecno, which I had never seen. Only later did I find out that the brand belonged to Shenzhen’s Transsion Holdings.

From a strategic point of view, Transsion has purposely avoided the hotly contested markets of Asia-Pacific and Euro-America, and instead focused their sales on the African continent; for this reason, they remain relatively unknown to consumers in other regions. However, to have taken up nearly half of the market shares of the African continent, and become the cellphone of choice for most households there, is not something that targeted sales alone can accomplish. Much market research attributes Transsion’s success to the way that their product design brilliantly satisfies local residents’ needs: multi-day battery life on a single charge, or Dual-SIM Standby, which was reminiscent of the wave of counterfeit phones from China in a decade ago. But of all these features, the most important one was the phone’s built-in camera system, whose research and development Transsion entrusted to Taiwanese company, MediaTek. During an interview, Transsion’s vice president, Arif Chowhury, went out of his way to mention that the secret to their success was their cellphones’ selfie-taking function, which had been tailored to adjust darker skin color, “brightening relatively darker skin tones, so that the photos look better.”(註2)

Opinions differ as to what sorts of photos “look better,” but the view that lighter skin is “better” than darker skin is undeniably a colonial one. The formation of such a view has its own, complex history, and there is a huge jumble of essays on the subject. Most influential is the classification of skin colors and theory of “devolution” constructed by German anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in the 18th century. In the third edition of his 1795 monograph, De generis varietate nativa, he develops a treatise on why Europeans’ “white skins” are actually in a state “uncontaminated by color,” whereas Asian and African people “degenerated” from white Europeans—such a devolution took them farther from civilization. (註3)

Even though this line of reasoning seems full of contradictions, today, most people fail to realize that the understanding of skin color prevalent in today’s world still bears a striking resemblance to Carl Linnaeus’ and Blumenbach’s categorizations, namely white, black, red and yellow. Obviously, unless one attends a Simpsons-themed costume party, it is impossible to find a group of people that can really be classified according to these four colors.

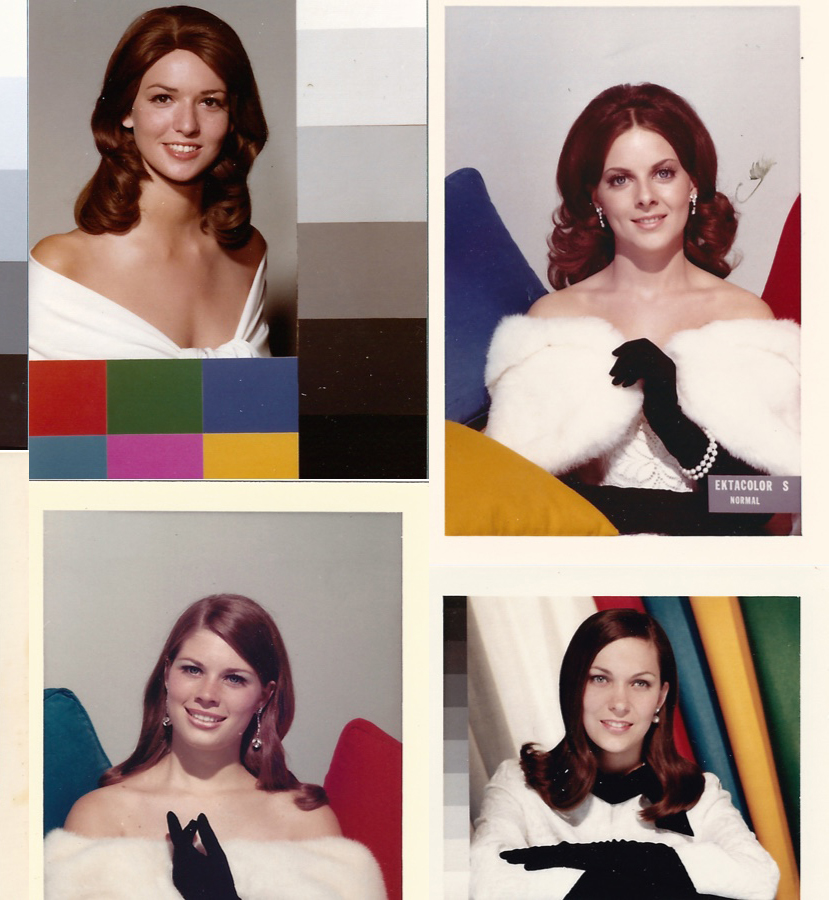

Both the classification of skin color and the belief that light skin is better are ideological constructs produced by a specific historical structure; in reality, they can do nothing to further research in any field, and will often even result in avoidable misunderstandings and social conflicts. The fraught problem arising from the relationship of skin lightness and image production are not limited to smartphones. In 1978, the film director Jean Luc Godard was invited to the Republic of Mozambique, which had just won independence from Portugal, to assist in establishing a national film institute, dedicated to propaganda. Godard quickly realized that the two most popular mediums for capturing images—Kodachrome and Ektachrome film—were incapable of accurately exposing dark-skinned people. He then tried to build, on the spot, a tape recording system, and state, clearly, that “Kodak film is racist.”(註4)

The reason that such film was then incapable of representing dark-skinned people in a detailed manner was that when Kodak was adjusting the light-sensitive photochromic pigment of its film, it used light-skinned women to calibrate skin tones. These models were selected specifically for their delicate features and fair skin; these color calibration cards, which became the industry standard, were called Shirley cards, and the models that graced their surfaces were christened Shirley Girls. Perhaps this outcome comes as no surprise: technological developments are usually born of consumer demand, and most of the customers who used such film were white Europeans and Americans.

Kodak eventually did adjust their product, introducing their Gold MAX film in the 90s—though not in response to racism, but because clients complained that their product was incapable of capturing the details of dark-colored furniture and chocolate.

Another, unfortunate thing happened in relation to Kodak in 1978. Its employee, Steven Sasson, registered the world’s first digital camera with the American patent office. Alas, Kodak’s management failed to immediately realize the revolutionary nature of such a technology; to the contrary, they believed it was deeply dangerous, and would jeopardize the analogue film industry, of which they were the proud masters. So they postponed the manufacturing process for such a camera. Everyone knows what happened afterwards; by sticking its head in the sand, Kodak lost its place in the history of images, and failed to survive in a world dominated by digital images.

The pervasive spread of digital images is intimately related to the development of image compression algorithms; the latter provided a method for easily producing and storing images, whereas the use of charge-coupled devices made it possible to view photos right after taking them. The power of digital images reached its zenith when digital cameras were combined with cellphone technology, not only obviating the status of photography as a specialized skill, but also, in the wake of the internet’s development, ushering in an age where taking, uploading, and sharing photographs has become a ritualized expression of each individual’s identity and taste.(註5) In this current framework, algorithms that capture and analyze facial outlines not only allow users to focus, edit, and tag photos, they also provide various photo and film-sharing platforms the power to process enormous amounts of data and surveille users.

The image’s transition from analogue to digital has thoroughly changed the symbolic meaning of photography. No longer does the photographer or filmmaker need a specialist’s knowledge of how to operate certain instruments—algorithms take care of everything now. Despite this, however, racist images continue to abound, for reasons that are not so different than when Godard discovered film was racist. It is not that machinery or light-sensitive pigments themselves have preferences or consciousness; the phenomenon reflects the biases of the engineers who adjust such pigment, and who code the algorithms. When such engineers design sensory systems, the data fodder with which they “feed” their algorithms is primarily that of light-skinned people. Consequently, such algorithms are incapable of detecting darker-skinned people.

Discrimination in contemporary photography and film is a complicated issue. We must move past the surface of the skin, go down beneath the pores, to where the deeper problems lie. When MediaTek helped Transsion to improve their camera functionality, the first thing they did was to build a new database of facial characteristics, one that was based on dark-skinned people. This kind of technological fix contains much symbolism—from the physical changes hardware and software one, to changes to technology, to the sociological impacts of colonial history, to the philosophical import of reproduction. When a Filipina-American internet celebrity was recently attacked by a horde of angry Korean netizens for a tattoo resembling the Japanese rising sun flag, yet such retaliation consisted of calling the skin color of people of Filipino descent ugly, our distance from the “light” seems to increase.(註6)

Du Bois once prophesied that the problem of the 20th century would be the problem of the color line, but he certainly did not expect that things would be the same in the 21st century; his imagination of the rising sun, in Beijing, perfectly resounds through time, with our own, contemporary situation. Perhaps to algorithms, the lightness or darkness of a skin is merely a difference in signal, but when platforms owned by a few are able to quickly influence the visual perception of millions, the technological recalibration of a medium’s discrimination will be thrown into more urgent crisis.