Browse

Once, returning to the mountain, I realised that Axiang and Amay had used cut weeds and leftover food to add to the garden bed, as they must have observed me doing. The garden bed looked very full, rich and abundant with this contribution, but on second look I realised: it wasn’t layered in the right order for sheet mulching. The weather recently was so hot, and with limited time on the mountain I was trying to think about how to deal with these new piles of organic matter.

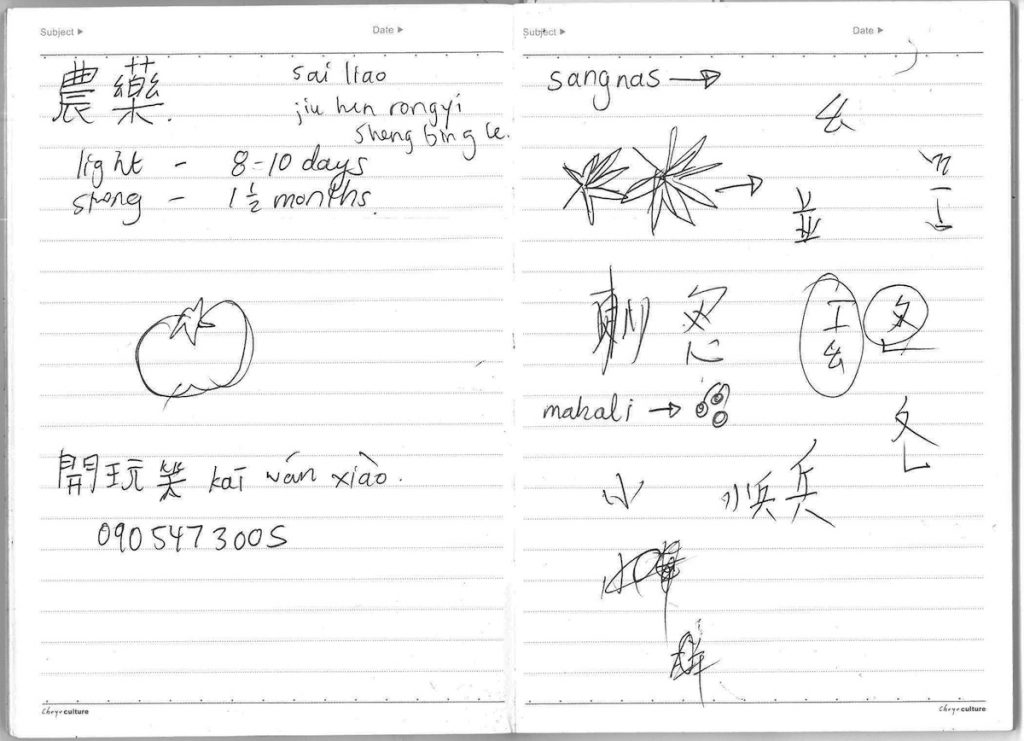

Because Axiang that weekend was at the bottom of the mountains, and Amay was sick and needed to rest that day, KCing made me lunch. During lunch, we had a conversation about it. He knew that something in the project was wrong somehow. He advised me to ‘fan guo lai’. At first I didn’t know what he meant. He made a movement with his hands, flipping something over. I had to try to flip the material over, creating the right order, though it meant a lot more labour. Then I returned to the garden, and I started to collect up the material. As I worked in the heat, layering the new material in the correct order according to sheet mulching, I kept thinking about this expression: turn it over, reverse, turn it over. It was an interesting expression to describe the miscommunication that was happening repeatedly between my host family and myself. (“Back and Forth: Misunderstanding”)

1. Plant Blindness and Migration

On the surface, some of the family’s lives outside of the mountain, seemed somewhat like my own (lack of) experience with growing plants or gardening. In my own case, I would consider that I have been a sufferer of ‘plant blindness’, and of ‘nature deficit disorder’. This was something Axiang, the mother of Amay, could tell when I was not able to remember what a plant looked like after she had shown it to me.

When I was growing up in Australia, I never planted anything in our suburban garden. What’s more, my parents never distinguished the Chinese vegetables we ate at home by any name. I remember asking my parents for more detail for a school project about what we ate one night, but ‘veggies’ were just ‘veggies’. I started to cook Chinese vegetables and keep plants in Berlin in 2015, trying to overcome this problem. In Taipei in 2016, I got a plant ego boost when I found out that a pot plant I had bought randomly at the flower market for its likeness to my idea of Taroko, turned out to indeed be a native plant from the Taroko area.(A fluke, or less a successful moment of plant visual recognition, than simply just ‘緣份’ or the fate? )

I wanted to learn more about the plants in the national park during the residency, and also carry out the exercise of drawing those I spoke about with Amay and her family.

In my own art practice, I often relate to my experience of being from a migrant family that has moved over the last four generations, from South China to Malaysia to Australia, which I also reflect on through my life being based in Taiwan. I often question what this experience means for my cultural belonging. It was interesting to shift my perspective in terms of thinking about, and when I was with, the Truku community.

Throughout this project, I learn that Truku people are currently dealing with shifting Truku identities through diverse modes, including ‘memory work’. Within this work is the issue of how the Truku people are sustaining their relationship to their local environment as its indigenous people. Through our various plant blindnesses, I reflected, as I always do, about my own belonging and connection with different spaces and places, as someone who identifies as being a migrant. More directly, I ask: where do indigenous and migrant subjectivities meet, when thinking about belonging and land?

When walking up and down the mountain with Axiang, she could point out a very inconspicuous looking plant and tell me that we could use its roots to make a tea. When walking along the main road in Xincheng, I asked her, “The Taroko Gorge amazes many tourists. But how do you feel when you see the Taroko Gorge?” Axiang replied, “Walking along the gorge for me is like walking along this road here”. She explained it was just a route in their daily life. I laughed at the contrast between these two places. Afterwards, though, I thought: maybe it means that she can look at the forest and understand its environment, just as I learn to read the signs and objects of the streets in a city or town.

Axiang didn’t just introduce me to native plants from the mountain. As noted, the Truku people in Dali-Datong grow exotic and cosmopolitan plants in their gardens. Axiang brought us a plant one day that only after some time did I find out was a plant which is characteristic of South East Asian cuisine, and that my great-grandfather used to cook with in a variety of ways, as part of his work in Malaysia.

2. Transplanting Memory

Building can only start from what is already there. The sheet mulching not only comprised of organic materials from the mountain, but also was to represent the memory of the place, as well as the process of our exchange.

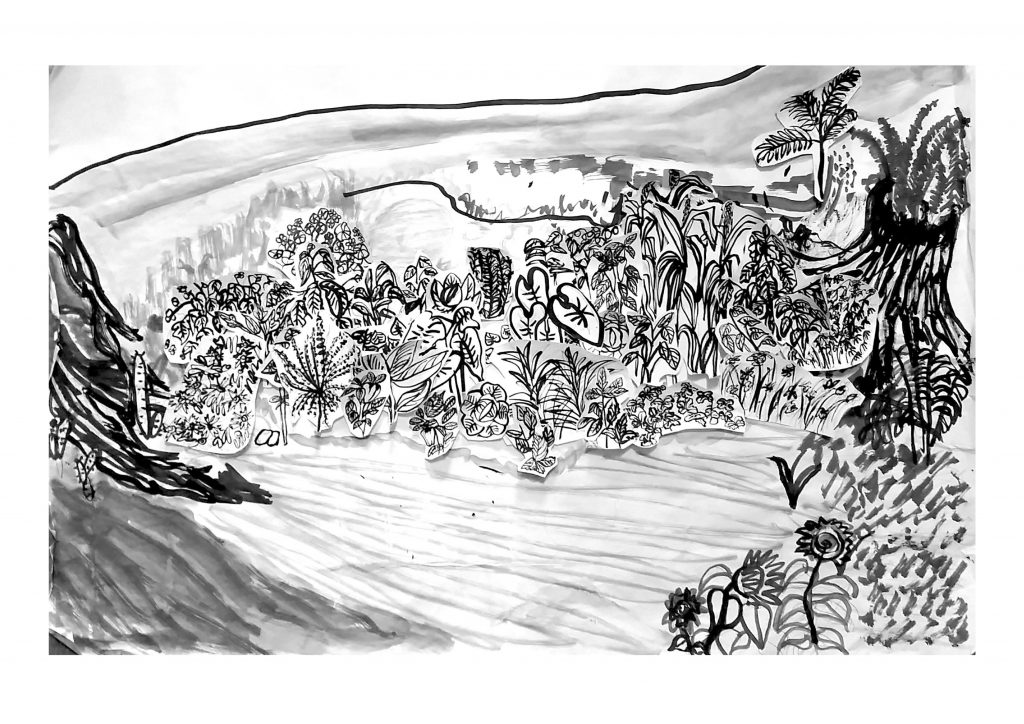

After collecting Amay’s family’s stories, I created drawings and writing of plants we spoke about in Chinese ink. The drafts and mistakes I made from this drawing process were added to the layers of sheet mulching on their land. As in my previous composting of my own mistakes, the stories become a basis for this new landscape.

In 2016, the Japanese maple tree got blown away from Dumuen’s house in a typhoon. However, the memory of our interaction still exists there, with Dumuen afterwards giving updates to me, through Chengtao, about the garden’s progress. It is as if a garden in the mountain does have the capacity to contain a collective memory. In a similar vein, along with sheet mulching a garden at Amay’s, I wanted to plant a garden that could grow the plants that Amay’s family shared with me, in their recounts of growing plants in the mountains, as a way to value and record their specific connection with the land.

Alongside plants and adding painting mistakes in the land, I also brought my own ‘calligraphic’ compost from Taipei to Hualien. Not only is ‘live’ compost a key component to catalyse the sheet mulching process, I thought of this action as the return of soil from the city to the mountain. Almost like a symbolic reversal, I made compost in the city, and returned it to the land where concrete gets extracted (from a mining site on the edge of Taroko National Park) and is subsequently used for urbanisation.

3. Inkwash and Watering

After the residency had officially finished, and I was in Taipei reflecting on the project, I became concerned. I was not only worried that the family felt alienated by what I had done, but also perhaps that the garden wasn’t going to look ‘good enough’ by the time we were to have the residency presentation in the mountains the following month. Not wanting to embarrass Amay, or be too misunderstood, I realised that the garden would need something more to express the idea of sustaining her family’s memories and stories, especially if some plants had still not emerged.

Accordingly, I decided I would attach bamboo sticks to the paintings and stories I had made on paper, and stake these in the soil, directly in the garden. This could represent an idea of what we had planted there, what could emerge there in the future, and at the same time, refer to the family’s past and existing connections to the mountains. I had found out during the residency that Amay appreciated painting, as she had shown such admiration towards Marianne’s paintings, and had invited Marianne and I to paint inside the guest house. Therefore I decided that showing my paintings of their stories at the site could potentially create more relevancy and identification for Amay and her family with the garden.

The last planting took place at the end of July, when I went to Datong with Chengtao to meet the Truku female elders (to discuss plans for The Cube presentation). I brought up the red beans that I had started growing from seeds in Taipei, as well as a goji berry tree and sweet potato, and some more turmeric root that had grown buds.

During the meeting, Amay spoke about how they realised the sheet mulching had made the soil very fertile. She told everyone that she had planted pumpkin seeds and other seeds in the space I had worked on, and they had already become sprouts. In another spot beside where we had been working, she had started to use the sheet-mulch technique herself.

After our meeting, I went up Liwu Mountain to plant the things I’d brought with me. Just as Amay said, there were signs of new life just starting to peek out of the soil. The plants I had brought from Taipei didn’t seem like they had completely established themselves, though it seemed like they were surviving. A few plants, such as lavender and mint, had dried out and died.

At the same time, KCing was already busying himself with pipes around the place. He came to me and announced he was going to link up this part of the garden to the water tanks (which collect water from the mountain spring). I had always wanted to ask KCing if he could help me do this, but never had the chance, always delayed by our language barrier and the other things we had to try to discuss. In any case, he was already taking the initiative.

He said, in his always comical manner. “We don’t know what you want to do, we can only know if you tell us what you want to do. But I’m clever, I know. You can say: KCing is clever.”

I realised the garden had gradually brought our actions closer together. I laughed, thanked him, and asked him if I could help.

He replied, “You work on your thing…“(你忙你的)

Epilogue

When an artist goes on a residency, maybe there exists the idea that they have to create something -build something- especially if the artist is used to creating installations, and tends to work with tangible materials. But the site of the residency is never mine: it doesn’t feel like mine to build on. In my art practice, I consider the act of building by way of Tim Ingold’s interpretation of Heideggar’s dwelling perspective: before you ‘build’ you have to dwell, and only through dwelling can buildings crystallize(註1). I interpret this building as contributing culturally, “through activities of cultivation and construction”(註2) in the community.

To me, in this residency, the act and method of dwelling is the emphasis. Furthermore, the site of this residency has been historically contested, and in different configurations continues to be. Dwelling within these contestations creates the means for which organic exchange with the community will take place. And it is only through dwelling with the family, whether in Dali/ Datong

(within Taroko National Park) and Xincheng (in the township at the bottom

of the mountain, at the edge of the national park),that I am able to share just some of the many complex instances that

constitute the Dali Datong Truku Community..

In this project in Taroko this year, there was a lot of awkward and amusing misunderstandings that occurred between Amay’s family and myself, due on one hand, to language or cultural barriers, and on the other hand, partly unexplainable, seemingly different logical perspectives about things. For me these differing interpretations can also be thought about through making something ‘reversed’, a way to express being in an exchange situation where one has to rethink, or reverse, one’s ideas about how they live.