Browse

Esther Lu: Maybe we can start this conversation by introducing soft/WALL/studs’ origin, like how it began and how you met each other.

Luca Lum: soft/WALL/studs (s/W/s) began in 2016 with four artists: Kenneth Loe, Weixin Chong and Stephanie J. Burt, and myself. We started renting the space as a studio space for ourselves; the studios provided by state-run National Arts Council Arts Housing, where you had to sign on for a few years with stipulations, was not an option – some of us had planned to leave Singapore in a year, and we wanted to avoid over-dependence of state structures. The original set-up had a lot of the elements that remain today, like the libraries, which was started as a way to share resources. As I recall, a lot of the ideas for the project space element came from Kenneth, and was meant to be an extension of generosity that flowed out of having our own studio space, and of not delimiting a studio space to simply a place of production, or separating it from other possibilities of use. Around that time there was a dearth of independent spaces running in Singapore; many events were “pop ups”, and it felt like the awareness and imagination around what supports art-making, had cramped. The scene to me felt overtly centralised and formal, dominated by institutional or commercial ventures, and that very clearly affected the kinds of projects and lives that were supported, limiting rhythms and visibilities. We felt we could offer something else on our own, extremely lean and humble, but different and enthusiastic terms, and we realised early on that offering this space to others was seismic in its own way, perhaps because its terms felt intimate, different, generous. Very early on, people like Kin and Chris came on board to show films on the rooftop. We were always surprised by the turnout, and I became aware that activities and our audiences were emerging out of pre-existing socialities, people who knew each other and hung out or met at gigs. Friends who were filmmakers, musicians, would just say, hey can I do something like this there? Our friends and peers began to propose activities – it all happened quite naturally, through some sense of affinity and openness. At the time, I had also just graduated from university and resisted (and could afford – or deluded ourselves that we could afford – to resist) getting a full-time day-job, which allowed me to hang out there, with some of the others, all the time, which was the foundation to exchanges and collaboration in a very felt, organic way. It was just about synergy and enjoying each other’s company, bringing about something in each other we might not have had otherwise.

Esther: So you were all just newly graduated at that time and trying to find a new position, or a new way of engaging in the art world by building your own space?

Luca: Generally we realised that we needed to create the room in which certain kinds of practices would be heard – where our practices could be heard, in tandem with that of others which might have had networks or currencies for exhibition or cultivation. It was a desire for autonomy.

Esther: Right, so you started renting this space and organizing things organically. And did you already have the name or have the kind of consensus that, OK, this is a collective, and we’re going to do projects together?

Luca: We’d brainstormed a few names. At some point I made an instagram account called “softwallstudios”, which was then shortened to “softwallstuds”. The name’s provenance came from two things – to specify the tone of the project and to suggest its structure. Part of the term behind “softwalls” came from wondering how we were going to display things in the main space. The initial idea was that we would use curtains or deploy movable walls. The name evoked a sense of porosity and fluidity of terms, which felt important – signifying a stance against hardening or ossifying the way a lot of institutions or organisations tend to, because if anything, I wanted it to always exceed its description. Regarding your question of how we decided to do things together, it began small, often by exploring an idea between two or three of the initial four persons, always with the understanding that whatever was made in concert with each other was another layer to our individual practices, that it enabled something within ourselves to come out through contact with another, or were actively about negotiating what it means to be together, to work together, in a way that extends beyond simply the work as an object.

Esther: And have you discussed having any collective goals or ambitions, or it comes really organically? Like, this is what we’re going to do next, and things just keep following up. Have you ever set a limit to what you do or what you don’t do.

Johann Yamin: I can’t speak too much for the beginnings of s/W/s since I’d only started attending things from 2017, and joined in 2019 when I was about to graduate from university. My sense is that a collective goal has never really been something at the forefront of our minds. I do think I arrived at a point when studs had already gathered its own sort of momentum – not in the sense of a collective unit moving singularly with a common aim in mind, but in the sense of how it’s come to be understood as a collaborative project, with individuals operating alongside each other, finding affinities and cross-contaminating each other’s practices and interests. s/W/s doesn’t necessarily operate as a cohesive unit all the time, and that produces interesting, tangential, and amorphous arrangements. So in terms of collective ambitions, it’s probably not so unified and I appreciate that and all its peculiar forms.

Luca: Historically speaking, there are many reasons for persons to collectivize, and I suppose unconsciously we meandered towards some of those historical goals, but at the beginning there wasn’t really an idea of a group or an identity – s/W/s was a thing we did, and it emerged and changed each time it was inhabited, discussed, enacted. The idea of collectivisation didn’t really come in until the second or third year, but the idea of creating a structure that built a room or sensibility where we could be understood was there from the start. At least in my experience of collectivity as it appears in art – paradoxically – can sometimes be a very flattening device (or mode of operation) – a large sector of the cultural sphere is engendered via neoliberal structures, histories of the left are obfuscated, fragmented, so collectivity often functions as a branding mechanism to build mystique and capitalise upon, as opposed to necessarily forming a structure or form working towards alternatives. When we first started doing things and becoming a bit visible, people wanted to know what we were about, but their lines of questioning often felt motivated by a desire to shoehorn us in a category so they could decide how they could capitalise or situate themselves in relation to us. I was wary of those logics, because they are premised on certain pre-existing hierarchies and a desire for novelty, and because s/W/s isn’t just a space, but to me at least, a doing (or undoing). I was also wary (and weary) of collectivities that name themselves before truly understanding each other, and without knowing where we each sat in alignment with one another. So for me the thing to do was to always be in process by retaining fluidity in our arrangements, even the way we wrote about each event. Singaporean art spaces and curators accustomed to a very starched, legible description (a kind of lie of accessibility) called it a s/W/s style, but it was more about using language differently and not enclosing whatever we were doing there by description. We also avoided something too prescriptive because the space wasn’t meant to behave like a white cube space anyway; in the early days, especially because a much smaller core group ran it, the priority was on intimacy, and a kind of unpredictability. I have to say that each time we are called together is a calling into being, each time we are named is a calling into being, and forms one renegotiation of the sense of the group. What holds the group together is a fretwork of alignments around queerness, questions around decoloniality, of the desire to see more robust discursivity, to reclaim a form of autonomy, and some of these grow with clarity over time, but only really through consistent being with each other, be it organising events, reading, hanging out, responding to an event.

Marcus Yee: As much as we have this mode of working alongside each other, along different tangents, it’s also interesting to see moments where actually we do come together to form coalitions.

Esther: I would like to ask the question about membership. How can anyone become one of your members? Like, what is the boundary of this community? How many members do you have now?

Luca: How many? Just like a (Asian) supergroup. It’s like 12 people now. Some are located in other countries.

Marcus: We regret it.

Luca: A really face facetious answer to the question about how someone becomes a member is that you would have to start paying rent.

Esther: OK. (A BIT STUNNED LOL)

Luca: Okay, that’s not entirely true. I think what’s happened over the years is that some people stick around enough to become accomplices to the project, to each other. I feel like that has become the baseline for how persons have remained. Like there’s this sort of sustained thing that you do together that is maybe only possible when you’re together and then you’re implicated in the group, and you choose that maybe you want to consistently contribute in a certain way. And I think that not many people ask to join, because it sounds like quite a task. And at the same time, it can also seem quite opaque as to what it means to join.

Esther: And so every member has to share the rent in a way, or?

Luca: If some can’t pay, it’s okay. Over the years we’ve found ways to redistribute the load.

Shawn Chua: We did visit that question a few times. There were models where people were contributing to different degrees in terms of rent — there were also members who may not be paying rent, but were contributing other forms of labours. The question about membership is an interesting one, because that actually questions the core of what it means to be part of s/W/s. I really liked what Luca said about being accomplices to each other, and there are so many permutations of all these dynamics, amongst the twelve of us. One of our early conversations when it came down to this question about rent and membership, is that if there wasn’t something easily legible, tangible, or articulable, then what made one a member? And that was an open question, I don’t think it was resolved formally. But then we found a certain kind of momentum, a rhythm of being with each other.

Luca: Now that you’ve put it that way, it makes me think of the question a bit differently. I agree that those conversations Shawn mentioned were essential for certain operations and formal processes. But there are some entities or friends who in an extended sort of way are also part of what makes s/W/s possible – because certainly some of the things we do aren’t for ourselves. And that’s where the community begins to bleed out and have some kind of stakeholdership, even if persons are not part of operations like paying rent or like contributing to programs. So I think when the bleed happens, when there are moments of investment from other people as well. I wouldn’t discount that from being part of the relay that s/W/s builds as well.

Marcus: To give one concrete example were discussions in 2018 surrounding fundraising and rethinking who our support networks with this larger community of studs are. That’s how our Patreon funding model came to be. In this light, it’s important to consider studs within an ecology of collaborators within cultural spheres.

Luca: Just a side note, we have a shared calendar of a few other arts groups and it’s called “Friends with Benefits”, so that we don’t clash with others when we organise events.

Esther: That’s really interesting. How would you describe your organizational structure in a metaphor? That will be my next question, since you mentioned this calendar of friends with benefits.

Shawn: A slime mold, that’s the metaphor.

Esther: Another one?

Luca: One of the earlier ones, was “a complex entanglement”, which came out of feeling really implicated with the enterprise, an implication that felt significant, especially doing care-taking, maintenance, lubricating labours as a female-presenting person. And being aware that one is implicated with each other, with the structure of it, in varying ways, ways that might also not entirely involve agreement. You’re always situated in relation to one another’s material reality, whether you verbalise it or not.

Esther: Since Marcus mentioned about the fundraising part, I’m really curious. How do you do fundraising throughout the years? And have you followed different strategies of your own to tackle this difficult financial question that is challenging to every independent art space? Have you got some government grant annually, or how do you run your private fundraising and how do you target your supporters?

Shawn: In 2018, we had a conversation about the costs of holding events in our space, and I remember at some point suggesting that it’s not a bad thing to offer a donation box and to have events be pay-as-you-wish, while still being quite clear about a suggested donation of a specific amount. Because I think oftentimes the labour of organizing isn’t acknowledged. When we have TheoryFILM events for example, we usually say we have a recommended donation of five dollars, it’s pay-as-you-wish. We also have drinks by donation and we’re quite transparent about what’s the financial gap that we need to cover each month.

Esther: And so that you make a financial report every month to your audience?

Shawn: Not to that extent, but we put a Post-it note on the refrigerator.

Esther: It’s a very subtle gesture. I love it. It’s like when someone tries to open the fridge to get a beer, and there is a reminder that oh by the way, you should pay.

Shawn: We did have a few more formal initiatives, like the Wearable Archive project – which was so much labour and pain, actually, just in terms of the coordination. Wearable Archive was a series of T-shirts with prints of events that had taken place at s/W/s. I think we still have some shirts available. So that’s one of the initiatives that was happening over 2018. And recently, we finally launched our Patreon account.

Luca: We’ve never applied for government grants to sustain the space regularly. The only time we got a grant was the NAC Capability Development Grant, specifically for an overseas residency at the Cemeti Institute in 2018.

Shawn: That was more for a specific project, rather than the logistical needs of the space.

Luca: Yeah. Those funds don’t go towards sustaining the space, at least not in the physical sense. They go towards building projects and relations, sure.

Esther: Well, it seems like you have been working on so many events over the years. You have quite a few different departments. You have the archives. You have a library and a screening program and many things. How do you distribute all the responsibilities here? How do you work together? Like, who is buying the toilet paper? Who is cleaning the kitchen? Just to start? How do you distribute responsibilities among yourself, and who is taking care of things?

Marcus: When some of us were doing a residency in Yogyakarta, we were asked a similar question. Who is buying the toilet paper? And the interview was aptly called, “Toilet Paper Interviews”, initiated by KUNCI. It’s to find out what goes behind the scenes in independent space and organizing. So… who really buys the toilet paper at s/W/s. It’s not me, but I have one person in mind. But definitely, how we organize labor tends to be by initiative at studs.

Esther: So there is no manager in that sense.

Marcus: In a way, because it’s less centrally organised and more affinity-based, where managers are those with affinities to particular projects or modes of working. For example, someone might be closer to working with finances or administration for rent and usually that person manages those aspects. But I think throughout the years we have had discussions about rotating labor, how to split labors more equally so as to pigeonhole ourselves and others…

Esther: But everybody has different strengths. For instance, when I was running TCAC, I wasn’t the one who was really in charge of the money because I’m really bad at it.

Marcus: Yes, there was discussion about a rotation model. I think it was the brainchild of Kin. He was thinking about how, even if you may not be the best at managing finances, the task shouldn’t only be shouldered on the person who is good at doing finances. Self-organising also means opportunities for people to learn from each other. But again, it’s still a hypothetical thought experiment. It has never been played out as such.

Esther: Has there been a struggle in terms of your internal organizational side of things, since you decided to depend on affinity?

Luca: To stitch the previous question with this question, I would say that at the beginning, especially when it was a much smaller group, people would identify s/W/s with very specific people. That visibility is double-edged, because suddenly you’re representative of something more than yourself, more than your work, and you have the power and responsibility to speak for it, with it. You carry it with you. In addition, how do you enable a structure you have built to support you, when a good amount of what you do goes towards supporting that structure? Some of the more formal structures have eased some of those processes, but questions of support, real dialogue that allows for exploration and play don’t ever go away. I think we have gotten better at identifying external collaborators we would like to give time to, but internal dynamics are always a matter of constant calibration. I’ve also struggled with the hierarchy of what’s considered part of artistic endeavour—organisational work, reproductive labour, work that enables work, is still very much undervalued.

Esther: I would like to continue this discussion from another perspective, since you mentioned this supporting structure. If we try to think in terms of spatial practice, what do you share all together in your space? What’s your collective property and resources? I read your website. You have a library there. But I’m curious to know what you truly share and what you kind of lend it to the group. Or, maybe, what will be your commons?

Johann: That’s interesting because we’ve recently been thinking about what kinds of resources we have that could be shared as a collective resource pool. For instance, s/W/s has supported small ground-up initiatives, such as reading groups; some community and activist groups have also used our space for organization, to hold events of varying levels of privacy. So space-sharing has been one of these things we’ve done. There have also been other resources as well, which tend to be more granular, such as ad-hoc technical support, equipment, or our collection of orange-coloured bowls — something we have an endless supply of.

Esther: Let’s move to things you have been doing, and those that keep you busy. What was the first project that was hosted in your space? What’s the best memory that you have and, well perhaps, what’s the craziest party?

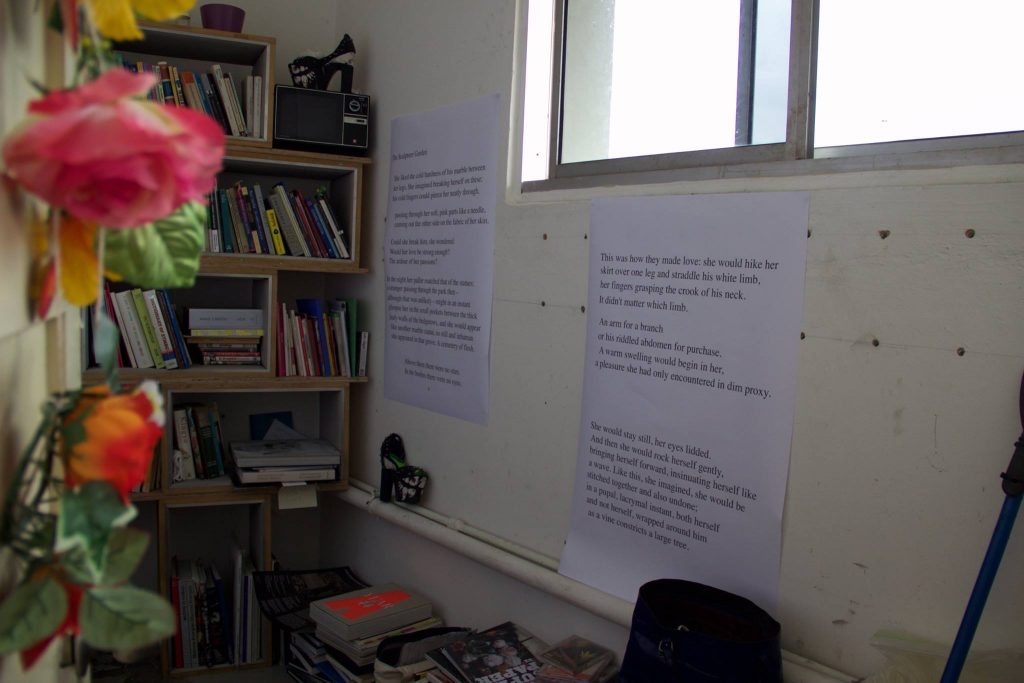

Luca: We decided to open the library with a reading event, called EX-LIBRIS LIB-ERRATA – “ex-libris” meaning “out of the library”. The four co-founders would take a book from the library and perform a reading. It felt poetic afterwards, as the event identified the library space (as well as the space and time of reading, and the reading/performing bodies) as active sites in entanglement with s/W/s. This was the first time that we understood the complexities within the space – between its functions, its layers, its gathering points. Overtime, especially with the regular library hours and events, we’ve seen these layerings and activations and developments accumulate as well as exfoliate.

Esther: That sounds cool. So it was a performance to begin with.

Luca: It was a relay of readings, some with more performative elements (with an awareness of our bodies and actions, the rooms we chose). It was the first time we started inviting people to come to our space, and I think the event really conveyed our sensibility. We still have to talk about the craziest, the favorite, and the most hated event, right?

Esther: Yes, please.

Kamiliah Bahdar: The event that stuck out for me was Xenoctober back in November 2017. It was to mark the centennial of the October Revolution. There was such an energy to that night – there were these series of happenings throughout the space, multiple nodes of things going on, with people moving about in all directions. It was disorienting. And it was made worse by the dress code, which was “dress uncomfortably”. That night really left an impression on me.

Luca: Xenoctober was the first event at s/W/s Kami was involved in. She gave a lecture in the emergency staircase, which lent well to the themes of her lecture; it also excavated a hidden level of the space we occupy, because the staircase is situated between our floor and the next. Kami, could you elaborate a little bit about the lecture you did for Xenoctober?

Kamiliah: I was in Medan years ago on fieldwork for my honours thesis that touched on the Malay sultanates in East Sumatra. In 1946, there was a social revolution that overthrew these sultanates. For Xenoctober, I played a recording of an interview I did with a politician who had genealogical ties to one of the sultanates, where he recounted history from his perspective. I played the recording while simultaneously reading from Anthony Reid’s The Blood of the People, a chapter detailing the night in which the sultanates were violently overthrown.

Luca: Xenoctober was an event that Marcus, Kin, and I co-organised. It was meant as a way to consider the aftermaths of revolutions and revolutionary thinking, especially because those histories are super fragmented in Singapore. Furthermore, these histories are complex, with contested strands, inheritances. How do you begin to locate yourself in relation to certain revolutionary timelines, what is left or remembered now? I want to hear what everyone really hated.

Esther: Haha, yeah, where is the nightmare part? It could be in many ways.

Shawn: I haven’t gotten to what’s hated yet. But I really enjoyed Altars, which was Marcus’s exhibition which took place in s/W/s. I especially loved the way in which the entire space became transformed during the entire period. How long did it go on for, actually?

Marcus: It was two months of installation, which is unthinkable for any exhibition space where usually an artist, if they are lucky enough, has a week for installation. Yeah, the whole project lasted for three months.

Luca: Imagine giant metal cages in this main space filled with trash. It was amazing what that mass of material did to space – it seemed to suck up all the air in the room.

Marcus: At that time I was obsessed with speculative fiction and ecological futures, a piece of fiction I wrote evolved into the installation project, Altars for Four Silly Planets. I had a little time in between getting out of National Service and enrolling into university, the idea came to me and I just materialized it, at least, when I had artistic ambitions rooted in making things. s/W/s was that place I could build and play. There’s also lots of palimpsest from the exhibition that has left its mark in the space. I still haven’t found a way to describe or relate to the project.

Shawn: Actually, Altars helped clarify certain boundaries of the space, because I remember there was some resistance by the landlord to the initial proposal of having one of the globes installed on the rooftop, or outside of the studio itself, and on the stairwell. I think of Altars not as an exhibition, but like an era, because there were so many stages of it. The long process of accumulation, the various interventions and other events that were cohabitating with it, whether it was the library or the game that was organised as a way to be oriented around the exhibition itself. There was a burlesque performance that interacted with the globes in a very strange way as well. Even in the aftermath people could collect objects out of the place.

Marcus: We realized how arbitrary those categories for objects were for ourselves, but also for the landlord. OK, just to give a visual impression of the space: There’s s/W/s and an adjacent storage space, which is covered by tarp and zinc roof on top of it. That’s owned by the landlord but we gradually began to use it as well.

Shawn: Marcus why don’t you show them the space.

[Esther had a virtual tour around s/W/s space from Marcus and Johann.]

Shawn: So you see there is residential space that surrounds us.

Luca: We have a temple right next to us, with its own celestial calendar of events.

Marcus: The people who call the police on us.

Esther: There you go. Lots of calls for police for the parties?

Marcus: We call them out for calling the police on us. We had one film screening where, because the film was quite pornographic in nature, the neighbors from a nearby block called the police to come over.

Esther: Did they actually see it?

Johann: Yeah, they could see the film because it was projected on a white wall on the rooftop, which the residential blocks overlook. So the residents were able to witness it all. Yeah. This is our lift.

Luca: Oh, it is the slowest lift in Singapore.

Marcus: It has an exhaust fan.

Johann: There’s the heart-patterned wallpaper in the lift.

Esther: That’s cute.

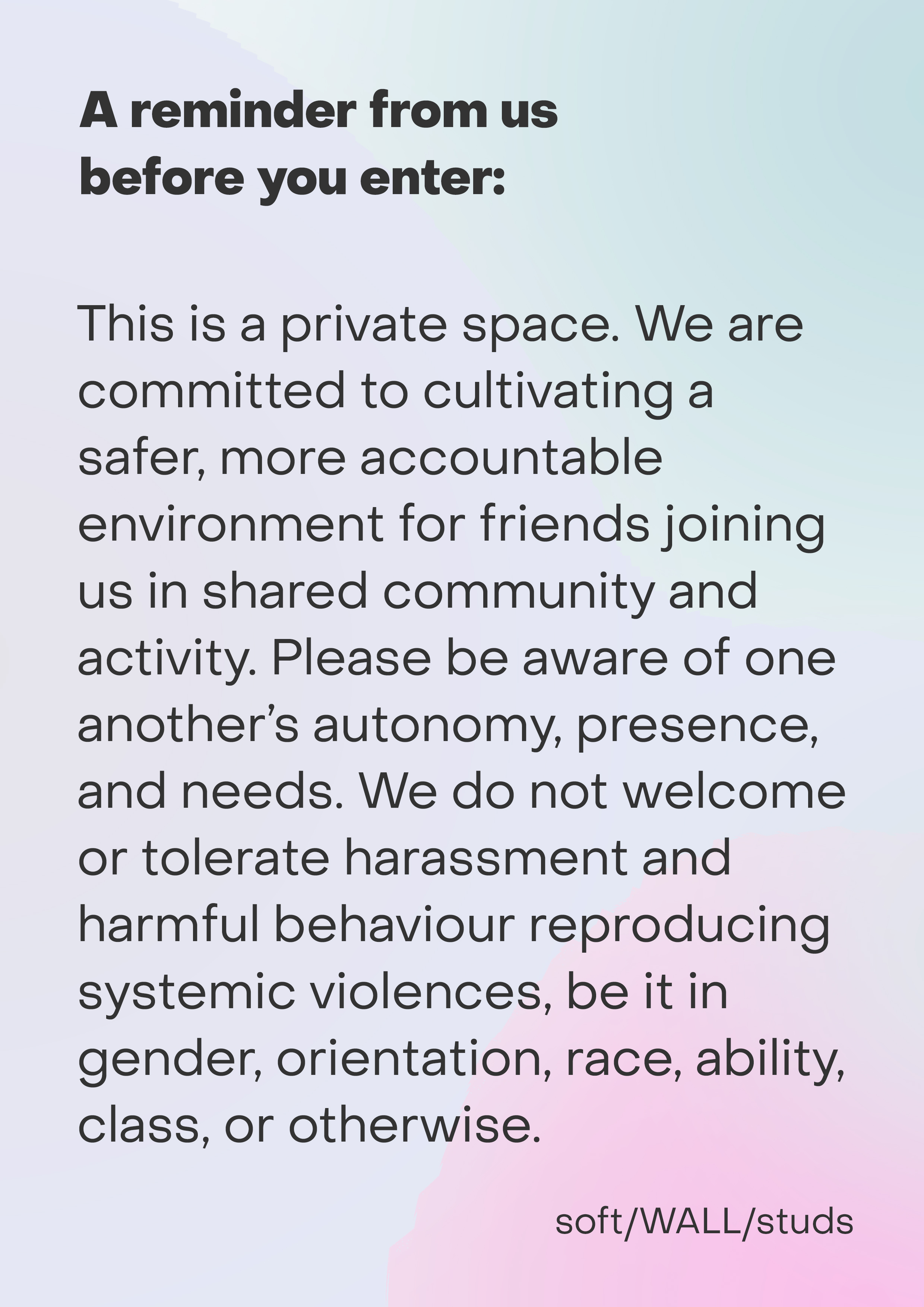

Marcus: Yeah. Some plants. And our community reminder.

Johann: It says, “This is a private space. We are committed to cultivating a safer, more comfortable environment for friends joining us in a shared community and activity. Please be aware of one another’s autonomy, presence, and needs. We do not welcome or tolerate harassment and harmful behaviour reproducing systemic violences, be it in gender, orientation, race, ability, class, or otherwise.”

Esther: Wow, it’s quite amazing that you can have 12 people working there together.

Luca: I mean, we don’t have people there all the time. And not all our practices require physical space or are trained on the material plane.

Marcus: Some have a more discursive reality.

Esther: Well, thanks for the beautiful tour.

Maybe we should move on a bit. I would like to know if there is any priority or focus on your programming like any sort of annual theme or it’s more like things would just come up and go quite organically. Is there any particular kind of focus of your collective practice in the moment or in the coming year?

Luca: We’ve been gearing up to run a few projects. There is a kind of thematic container around repair, care, distended timelines. But to be very honest, there very rarely is… there is some planning in advance, but as for seasonal, thematic, not really. Usually there are pet interests with shared resonances that gain momentum. Sometimes there are solo projects that are a bit more introverted, which others come on to support (even in small important ways, such as enquiring if the person needs help with any duties). That’s how I see it anyway, and I’m also interested to see how others see the seasons. I would also say that after the iteration of s/W/s where we had four or six central persons, there was an effort as Shawn and Marcus have mentioned, to organise ourselves so we could account for, and share labours. I feel like that structure has marked the biggest seasonal change for me. There is continuity, for sure. But there’s a difference in form now (with this in mind).

Marcus: Is this a question about futures?

Esther: My question is not exactly about the future, but how do you move from season to season, if we borrow the term from Luca, more like seasonal planning or focus. Yeah, but I guess I get the sense of fluidity in the nature of your collective and probably that’s how things keep forming and transforming. I would like to review the changes and developments of your collective from the evolution of programming, I guess.

Luca: I suspect also there was maybe some resistance at the beginning, especially to that kind of seasonal planning because it felt very…

Esther: Too institutional?

Luca: Yeah. Over time we recognized that certain projects require different momentums, some might work best with more foresight.

Esther: I think it’s really special of you as a collective. I feel there is a sense of flow, a sense of trust, a kind of chemistry that keep you together. And it’s just quite clear that you work as a group. I can feel the bond. And I think that’s quite amazing because I know you guys have very different backgrounds and practices. Seeing that bonding part is quite amazing. And I would say that’s the best value of this collective. I don’t know if you have any other opinion…

Shawn: I’m glad you said that – at the same time, I don’t want to overstate the amorphousness of our organization because actually there are certain kinds of orientations that we do take up. I like what you talk about flows, because in a way, I feel like that’s how the conversations begin to contaminate or mutate also. It’s not at all a completely random, Brownian motion process with particles drifting in the room, because to come back to the language of accomplices, there are certain kinds of shared investments, shared stakes. And if you think about it as a kind of prism, almost, then we see the ways in which a project begins to become refracted through our different investments, occupations, and perspectives. How they continue to then become in conversation with one another.

Marcus: I think about bonding. I think karaoke brings us together.

Esther: Oh, really? Is it really a common passion of yours?

Marcus: That is where the flow comes through.

Esther: Well, I did know that. Karaoke! What is your theme song?

Marcus: Different individuals or groups have different songs.

Esther: Name the song.

Luca: Kin is always doing the Phantom of the Opera. Once the police came because Marcus and I were singing Björk very loudly. We sang It’s Oh So Quiet, which is not a quiet song. I think a lot of us are very conscious of not doing things because of perceived importance. We work with what the affinities are, and where they intersect or form interesting dynamics. And sometimes that can mean that activities can be very capricious and sometimes they fall apart, don’t get followed up on.

It’s actually funny that you brought up chemistry; I feel it’s the only way we feel compelled to do work with another. Great chemistry to me is about a generous recognition of each other’s position, it requires a strange kind of intimacy perhaps, a bit of a dance, a bit of… shadowing work? – It’s recognising that we each occupy specific locations – material realities, timelines. Investigating the specific granularities of my life, its minor feelings, and the resonances and tensions of those things with others and in wider and deep structures is how atmospheres shift, a stranglehold of “now” may be ruptured, how I might bring out something hidden or unbidden within the matrix of my person. Interestingly, I haven’t thought of it as the defining thing about ourselves until you have pointed it out.

Esther: There is a very strong sense of caring among you, and that is very powerful.

Luca: I mean, we definitely fight, don’t get me wrong. But at least for me, perhaps there’s a feeling that not everyone understands the situation in Singapore the ways we do, and that’s why our relationships with each other are important. I do wonder what the afterlife of this project would be, what its next steps, deformations or ruins could be.

Esther: Because I feel it’s quite a nurturing process for each of your individual practice, and rewarding as well. It’s like you have this shared investment, and each of you are also rewarded a lot from different learning patterns, different resonances, as how you put it.

Luca: I guess it became really clear to me that it was an education that I wouldn’t have gotten anywhere else. Because you are fully implicated in the politics of whatever is going on; you realize immediately the impact of thought or action on the people around you, and maybe sometimes people who have a much more gallery-based practice, for instance, are perhaps a bit removed from where and how a thing goes into the world. It creates an intimate discursive community. That is quite a specific thing that has emerged.

Esther: And that really sets you apart from other independent art spaces in Singapore, right?

Luca: I think we have very different horizons. Very different desires. And also the terms of visibilities or legitimacy we aspire towards. For instance, we say no to a lot of things.

Esther: Like what?

Luca: Very early on, people wanted to put us on listicles like “these are the top five new art spaces to look at now”. We understood the excitement, but we also just didn’t want to be part of that economy.

Esther: Well, then, how do you position yourself in this ecology of art in Singapore?

Marcus: I have two points. The first relates to seasonality. To contextualize, there’s an oversaturation within the arts in Singapore, a demand for production that manifests as constant scheduling with an event economy. Where studs comes in, in relation to this kind of ceaseless flow, is its capricious rhythm. Independent organizing frees us from the pressure of scheduling with a regularity that’s often demanded from institutions. For example, an exhibition turnover every three months. Casting aside this pressure allows us to cultivate thoughts and work on different kinds of temporalities. For example, focusing on daily activities like maintaining the space or hosting people at a library. This low frequency organizing is important for us. The second point relates to refusal, when we say no. One of our biggest ‘no’ is regular funding from the main state arts funding body in Singapore. I think other people would have their opinions on why we refuse. Personally, it’s the kind of stakes involved in taking on a regular funding from the national arts council and trying to redefine what we mean by independence or independence of thought, independence of production.

Luca: I agree with Marcus. This might come out of as a bit critical, but because of the way Singapore’s art scene was streamlined and centrally managed, especially from the 90s onwards, [with the desire to coax forth a creative economy for the global city] there’s a sense of an unquestioned set of norms around what it means to produce and to be productive as a cultural worker, as well as to what your affinities are. So the arts can comment on politics but still be a very depoliticized space – which itself might not just be a problem that’s isolated to Singapore; it’s a symptom of neoliberal capital. And that’s not the kind of thing that we’re interested in. For example, we have some affiliations with civil society.

Esther: I see on your website there are lots of fund raising links.

Luca: I think Marcus and Johann can elaborate on that bit more. We always try to parse the relationships between art and life and politics. But we are also quite strategic about how we do it (because of certain sensitivities, perceived or otherwise) events might be opaque in description, a bit fugitive.

Esther: Have you ever got censored?

Luca: Censored? Beside the times the blocks opposite called the police? We have been quite careful, [and we have ways of keeping more controversial topics closed-door] but we haven’t had a certain specific kind of event that has attracted a very specific kind of controversy which makes people want to…

Esther: Over politicizing it?

Luca: Sometimes what is regarded as censorious and political in Singapore can be both narrow and ambiguous, (and that depoliticisation of the everyday is not coincidental). That means that very specific kinds of artistic production are also seen as subversive or overtly political gestures. Some of our activities which include reading critical theory and leftist histories together, more introverted gestures, more about building a kind of capacity can be elided. A lot of our strategies have gone that way instead.(註1)

Shawn: I think being apart from these frameworks, such as those by the National Arts Council, means we can host a lot of our activities and gatherings as semi-formal, or hold them as private events. That frees us from the usual licensing procedures, or from having to put on certain kinds of advisory notices that are usually expected of events in the context of Singapore. The term “independent” is quite interesting, and I feel quite ambivalent about the term because “independent” tends to position the space as if it were a radically isolated thing. But I think “independent” signposts a certain kind of freedom from the regulatory structures I described. Going back to what Luca mentioned earlier in terms of civil society groups, I’d like to think about it as being free from the usual ways in which art spaces are framed, which allows us to then build these communities, or reorganize what the boundaries of these communities are. That way, we find accomplices in other “sectors”, that might not necessarily be seen as the usual accomplices of the arts. So I think that’s what separates us from other spaces.

Esther: I’m interested in this conjunction of life and politics or society at large in terms of how your practices engage with other social groups like what you do with the donation web page. I think it’s quite amazing that an art space is presenting this kind of external links and references to further share a political view or their social causes. How did you come up with this decision that you would have the visible support to other social causes and movements? Is there any sort of collaboration or network that you are trying to build there? Or, what was your intention?

Luca: I think for Amplifications and Recirculations, maybe Marcus and Johann can speak about that a bit more. In general I’ve realized that we need to build coalitions. Some of the people we’ve worked with become this extended network of relation and possibility towards certain ends that you obviously cannot do alone, not even as a collective arts group. It’s very funny that you brought this up now because we have all just been alerted to an incident where this sort of coalition of groups and individuals are being mobilised to respond.

Johann: For the links you’ve pointed out on our webpage, they’re a part of Amplifications and Recirculations, which is this two-headed initiative that’s being hosted on the studs website. Many pre-existing inequalities were magnified during the two-and-a-half month lockdown that Singapore’s just experienced due to COVID-19, and numerous initiatives have emerged to provide aid to precarious or marginalised groups that bore the brunt of the lockdown – such as the migrant community or those vulnerable to domestic violence. Some of us at studs wanted to amplify these organisations, fundraisers, and initiatives that were already doing important work on the ground. So first and foremost, it’s an initiative about other initiatives, about recirculating attention towards these networks of aid.

We started with Amplifications, which was a consolidation of links to these initiatives on a single webpage. We listed these organizations whose work we supported, such as AWARE or TWC2, or initiatives we wanted to amplify, such as wares’ Mutual Aid spreadsheet. Shortly after that, we developed Recirculations, where we tapped upon our own networks of cultural workers to have their artistic contributions published on a webpage alongside their “asks”. The idea was that as cultural workers, we could help direct attention to ongoing initiatives through artistic contributions from the community. The listed “asks” therefore allowed a cultural worker to request support for specific initiatives already listed on Amplifications or elsewhere, and served as a space for them to voice out if they also had needs during these difficult times.

For Recirculations, we encouraged cultural workers to contribute the residues of their projects, or the scurf from one’s ongoing artistic practice, be they images, texts, sounds, links, videos, and so forth – this way, contributions were not predicated upon the logics of continued artistic production during pandemic time, when many were at capacity. Throughout, we also wanted to acknowledge the potential needs of cultural workers – we hoped to avoid delineating unhelpful saviour-saved dichotomies, but instead recognise the varied registers of needs from various communities, within our own or beyond.

Esther: Those are really beautiful gestures.

Luca: Going back to what was just said before, it’s important to resist silos, silos of individual persons, silos of knowledge… it’s difficult but important. One might say there is a kind of ideological limit as to what a lot of mainstream artistic activity does in Singapore. Singapore already operates as a zone of exception, and the arts and politics within it are also partial to that. Breaking silos down and demystifying the mystique of the artists or the mystique of artistic work, being a lot more real about certain structures, then also allows for another kind of possibility and another kind of horizon.

Esther: We are really in a special time now. What will be your next move after this COVID-19 thing?

Marcus: For the rest of 2020, we are also consolidating a bunch of programs. Over the past two months, we have begun to think of s/W/s as a site of mutual care, and trying to examine what that entails. There was this mention of the themes of repair, redistribution, of wellness, and portals. The point is to seize the opportunity of these discussions that have floated during the pandemic, since, as many commentators have pointed out, the coronavirus is an X-ray on existing inequalities. Specifically for the arts and culture, questions of value and remuneration have been raised. We also want to address how we could create more commons with other groups in cultural spheres and civil society. I think that’s the orientation for the next few months, if I can provide some rough contours.

Esther: Thanks so much. Before we end this interview, I would like to ask if there is a song that you as a group would sing for the audience in Taiwan, what will be this song?

Luca: I was gonna say a really cheesy one.

Johann: Say it.

Luca: 月亮代表我的心。[everyone laughs]

Luca: s/W/s is a satellite. Our influences are tidal, subliminal.